Posted in: Comics, Review | Tagged: ed brubaker, Elizabeth Breitweiser, image comics, Kill Or Be Killed, Review, sean phillips

Death Comes Ripping: Kill Or Be Killed TPB Review

"WHAT HAS HAPPENED TO ED BRUBAKER?!" I'm dropping the just released trade paperback of Kill or be Killed (With Art by Sean Phillips and Elizabeth Breitweiser) and backing slowly away. "I know I've been gone from comics for a little while, but surely he hasn't gone FULL MILLAR in my absence, has he?!" I'm shaking on the floor rocking back and forth, clutching my knees and begging the comic gods (who, for the sake of this dream sequence are played by Burgess Meredith as Jack Kirby and Jimmy Stewart as Will Eisner) to prove me wrong. To wake me out of this angry, white boy revenge fantasy and assure me that Ed Brubaker hasn't taken it upon himself to do a gritty, pulp remake of Wanted. (Remember Wanted?! Eminem sodomizing you and casual racism? 2003 was such a quaint time to be a fan of the funny books)

Thankfully my years of experience dealing with extreme anxiety and depression have gifted me the ability to maintain a stiff upper lip, while closing my eyes and thinking of England. Perhaps even more thankfully, Kill or Be Killed is longer than 4 pages so it quickly becomes gloriously, reassuringly clear that this isn't a sink into a Millar Morass but is actually classic Brubaker/Phillips style bait and switch.

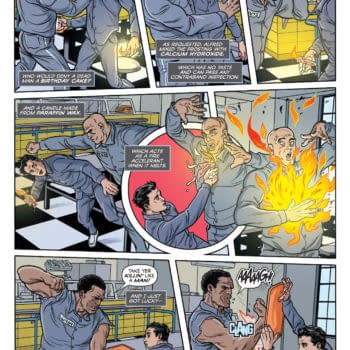

The story follows Dylan, an angsty somewhat sad sack graduate student in NYC who, following a botched suicide attempt ends up being confronted by a Demon with demands. Dylan has to pay back (to the Demon apparently), lives in exchange for his own life that he tried to take. Not just any lives will do, the Demon wants the bad ones. The deal is one baddie a month, though it's not clear how many months (lives) are needed to balance the scales.

Dylan doesn't want to believe it, choosing instead to assume that he is just going a little crazy and that it wasn't a demon that broke his arm, but it was probably just the suicide attempt (leaping from a building in a New York City winter). But when Dylan gets deathly ill as the end of his first month under contract from the hell beast, he comes around. An apt and fairly easy victim is the first, but as we can tell from the non-linear storytelling (done so under the narration of Dylan who apologizes for his tangents) the targets mount up from there both in criminality and difficulty.

Along the way are Dylan's roomate Mason and Mason's girlfriend (and Dylan's best friend) Kira. We're also shown that Dylan's father used to be an artist for pornographic sci-fi and horror mags from the mid 20th century, which starts off as character backstory but by the end of the trade starts to morph into possibly something more.

Kill or Be Killed is about a thousand different things at once. It can be read, celebrated, studied and dissected on levels upon levels. It would be unfair to the work to say, "Oh it's just another Brubakerian crime story." No idea who would say that, but there are people who claim that Bad Religion has only ever released one album twenty five times over the last thirty years. People say a lot of dumb things.

It's the perfect marriage of the different styles and forms Brubaker has been working in over the years. It's the confidence of a creative team not merely hitting their stride but demolishing it. It's got the creeping dread and lurking horror of Fatale, mixed with the tortured past and the "OH SHIT OH SHIT WHAT DID I JUST DO?!" of the best of Criminal.

I mentioned earlier that the story is something of a bait and switch. That's because KoBK starts off very much in the vein of "I am the avenging angel of justice. You are wicked and I am fury", which is at this stage in our culture and especially in comics, incredibly boring. But it quickly morphs into "I don't know what I'm doing and I think I'm going crazy but I have to murder this child molester or a demon is going to kill me", which is far, far more interesting.

Also as mentioned earlier, the story hops around in time from within the first person narration. Through this lens Brubaker plays with narrative tropes and is able to create an even more engaging and mysterious tale causing the reader to wonder "WHO is this character speaking to? Is he speaking to US? HOW? WHY? WHERE?" At one point Dylan mentions that he obviously didn't die because he's telling us the story. Can we trust this? Can we trust anything through Dylan's eyes or mouth?

Dylan's multiple suicide attempts make him appear as an emo Lane Meyer. And despite just comparing him to one of John Cusack's most likable roles, Dylan is maybe Brubaker's least likable protagonist. Dylan is a self absorbed, sad sack; depressed because he's 28 and in Graduate School while other people his age already have lives of their own. You're only allowed to be that mopey and dramatic about your lot in life versus that of your friends when you're in High School, Dylan. Dylan passes himself off as the tortured, literate scholar; the secret macho man with the powerful penis gun in his pants. Dylan dressed all in black with his just battered enough to look rugged face and wild, fanciful bandages compared to his roommate, a grinning, yuppie ponce in a polo shirt with a parted, shoulder length Bradley Cooper 'do.

Dylan has a crush on Kira and personally I found his longing to be more than a little gross and boring. Maybe I'm just over sensitive, hurt, twenty-something, English Lit boys with their pain and their "incredible women" who are "so unique". Dylan seems like the kind of guy who likes to have sex while listening to Neutral Milk Hotel and then cry afterwards. Or worse, Bob Dylan.

Another minor criticism is of the focus of Dylan's first outing as avenging street demon for hell. Dylan selects the brother of one of his friend's from childhood. His friend (Teddy) had awkwardly confided in Dylan that he was being raped by his older brother when the two kids were both too young to know what was going on or how to talk about it. The story goes that Teddy grew up and became a homeless junkie who froze to death on the street. While this creates a neat, convenient target for Dylan's maiden voyage, the "abused kid turned dead junkie" narrative is a stale and tired one. It helps cement an idea in our culture that people who've experienced trauma in the past, self destruct as they grow older and that the homeless person you just passed on your way home from the cinema is there because of an abusive childhood. Just like when people assume that all sex workers were either molested or have daddy issues, the notion that street junkies are debris on the human highway because of molestation and traumatic upbringings are over simplifications of many complex issues.

That all being said, this isn't a "slice of life" comic, nor is it purporting to be a factual, documentary. It's genre and genre relies on tropes, and that's not inherently a good or bad thing. The Teddy backstory works in KoBK, setting up our protagonist with a personal bit of revenge to mete out and creates an easily digestible baddie for the audience to rally against (particularly when following his death, the cops are able to break a whole child porn ring because of it.) I don't genuinely think that in the conscious mind of the people who read KoBK they are going to say "Oh well that settles how I feel about homeless teenagers then" and I don't want to be accused of trying to pointlessly rip apart something to show how sensitive and caring I am. What concerns me more than the changing moods and perceptions of the vast majority of people who are viewing trauma from the outside, is how people with trauma view characters and characterizations like this. People who've experienced deep, horrible trauma in their childhoods and are working to put together a life for themselves against the odds see themselves reflected in the culture around them, a culture that says "This is what you are. This is how we see you. Alone and unloved and dead on the street." It's hard to enact the difficult, positive change from within to fight against those past demons when all you see are messages saying that this is what happens to people like you. This is what you should expect from life. Not "this is what you deserve" but "this is what you get."

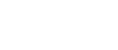

Speaking of tropes, Brubaker actually has a lot of fun subverting them as we see time and again as Dylan finds himself in classic revenge/vigilante scenarios, where a bad ass one-liner precedes an underdog flipping the script and reigning down bullets and fury like Rambo on a bad day. Dylan gets into these situations and always manages to do the opposite of what the reader expects (usually get himself beat up or run away).

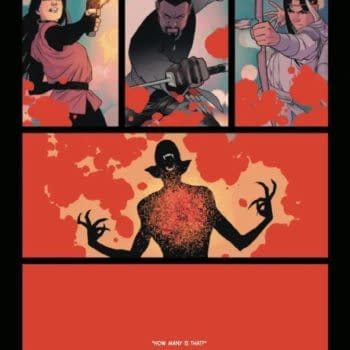

The art in KoBK is really magical, which is a funny sort of word to use for a story like this but it really is. Phillips's artwork is sublime and Breitweiser's colours combine to make cityscapes simulataneously warm and cold; they glow. Dark rooms are hushed and somber, rooms lit by one light feel like a candle in a monastery. The atmospheres conveyed panel to panel tell as much of the story as the narration or visceral action. While the look of the demon mixes classic and modern horror, looking like The Babadook went to Japan by way of Norway with Robert E. Howard.

Innocence and brutality are conveyed with equally stunning and captivating artwork. A post-coital scene with Kira and Dylan features some nudity on the part of Kira. It's striking and notable because the nudity is so out of life, nothing pointlessly titillating or gratuitously erotic. The way Kira moves around the room as she gets dressed and the angles we watch from, nothing feels voyeuristic or cheap, it all feels beautiful and natural and wonderfully, utterly human. That human side of sexuality and of the two main characters is an important one that is kept alive well throughout the work, serving to show the stark contrast in the world Dylan shares with his loved ones (and his memories) versus the one Dylan shares with the Demon (and in a way, his memories again).

The trade ends with a quiet bit of madness, a whiff of insanity, just enough to make you sit up and straight and demand to know where the next issue is. Well you're in luck because the next issue is out today! Go and get it already!

[rwp-review id="0"]