Posted in: Comics, Recent Updates | Tagged: Comics, dc, gail simone, relaunch

Give Batgirl The Chair by Eric Glover

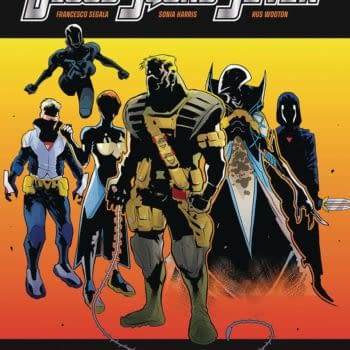

Ever since DC Comics announced a seismic shakeup of its entire book line for this September, promising a remix of character histories and costume designs to give its universe a more contemporary flavor, the move has sparked an incendiary reaction among readers, with one particular change fanning the most flames: DC's decision to return the paraplegic Oracle to her previous role as the able-bodied Batgirl. Because of the already slim share of characters living with disabilities in the DC Universe (or DCU), the sudden dismissal of Oracle's paralysis has not just been a point of contention for some fans, but also a puzzling contradiction to the spirit of DC's relaunch announcement:

"[The relaunch] will introduce readers to a more modern, diverse DC Universe… All stories will be grounded in each character's legend—but will relate to real world situations, interactions, tragedy and triumph." –Bob Wayne, Senior Vice President of Sales at DC Entertainment

But aside from shuffling a few more black characters into the spotlight, DC won't be making any huge strides forward in diversity, leaving the meat of its heroes classically white, male, heterosexual, and possibly even more able-bodied once the relaunch hits. The loss of diversification offered by Oracle—a hero borne of a "real world" situation both tragic and triumphant in nature—is a disappointing step back for a company that once took pioneering leaps with the Batgirl legacy.

The rise, fall, and rise of Barbara Gordon

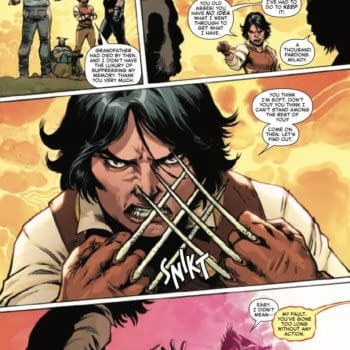

Batgirl was first brought to comics and television in the 1960s as the alter ego to Barbara Gordon, a sharp-witted young woman with an altruistic appetite for crime-fighting and an independence that personified the essence of women's rights advocacy during the time period. Confident, fresh, and vibrant, Barbara Gordon was a self-made superheroine that operated independently from Batman and Robin, and took no nonsense from either. Her character was so successful that when she was off-handedly paralyzed from the waist down in the 1988 comic Batman: The Killing Joke, fan reaction to the story was divided, and stayed that way through present day.

Although the canonization of The Killing Joke—in which the Joker shoots Barbara through the spine as plot fodder—has never won universal acceptance, DC editor Kim Yale and writer John Ostrander used the story as an opportunity to positively reposition Barbara in the DCU. In 1989, the former Batgirl became the now-iconic Oracle, an expert computer hacker and information broker providing invaluable intelligence and assistance to superheroes on the frontlines. From Yale and Ostrander's retooling onward, Barbara evolved personally and professionally, overcoming the depression brought on by her paralysis and realizing her remaining self-worth as a brilliant and capable crime-fighter. Along with being tapped by the US government and the prestigious Justice League superhero group for her services, Oracle has most notably founded and led her own female fighting force in the comic book Birds of Prey.

Needless to say, Oracle's prominence and popularity as a wheelchair user—while holding her own against acrobatic and super-powered peers alike—has been an unparalleled leap forward for disability representation in the DCU. Barbara's refusal to be victimized by her paralysis imbues Oracle with immeasurable symbolic value, as both a comic book champion for those with disabilities and a statement on how those without should treat them. The DC superhero community interacts with Barbara as an equal, and often relies on her to pave the way to victory against some of its most formidable adversaries. For about the past 20 years, DC Comics has asserted that a paralytic Barbara is not only irreplaceable in the never-ending battle against the bad guys, but fundamentally necessary in it. At a time in which 54 million Americans with disabilities are largely marginalized or, more often, completely ignored in entertainment, DC Comics has implicitly argued that this part of the population is just as important the rest, and certainly deserves to be recognized as such in its stories. At least, that's been the case so far.

Stopping short of science "fix"-ion

What stands out as even more remarkable about DC's use of Oracle up to now has been its consistent commitment to her bodily condition, bearing in mind its universe's fantastical and science-fiction-based rules. Given that futuristic technology, time travel and magic make injury and death somewhat small potatoes in this line of storytelling, it's been nothing short of groundbreaking for DC to remain devoted to narratives about the physical and emotional challenges of Oracle's paralysis—sending a message that even in a genre like DC's, people with disabilities were still relevant enough to include. Likely it was Yale and Ostrander's progressive precedent that inspired DC to exercise 20-plus years of restraint on the matter, resolving not to consider Oracle's situation a burden to its writers or her comic book colleagues. Instead, despite the various—and easy—plot means available to put Barbara back on her feet, DC had commendably chosen to celebrate the unique role and contributions her disability brings to the table.

But DC writer Gail Simone, who will be putting Barbara back in the boots with Batgirl #1 this fall, has taken the reverse perspective, asking how it would be "ethical" to leave the character paraplegic when other DC victims of violence have been healed through advanced science or supernatural band-aids—effectively deeming the socially conscious reasons behind Oracle's paralysis insufficient:

"Arms and legs get ripped off, and they grow back, somehow. Graves don't stay filled. But the one constant is that Barbara stays in that chair. Role model or not, that is problematic and uncomfortable, and the excuses to not cure her, in a world of purple rays and magic and super-science, are often unconvincing or wholly meta-textual. And the longer it goes on, the more it has stretched credibility." – Simone in a Newsarama interview on the controversy

Yet Simone's implication that meta-textual reasoning has been reserved for Oracle alone—or that DC's creative integrity is somehow being questioned by it—rings somewhat false. Until now, DC hasn't healed Oracle through an outlandish plot contrivance for the same reason Superman's kryptonite allergy won't be "fixed" by permanently dressing him in a protectively lead-lined suit, and the death of Batman's parents won't be "put right" with the comics' life-restoring Lazarus Pit: In reality, using on hand sci-fi measures to erase our heroes' most pressing challenges undermines what keeps them fundamentally appealing. Superman should be vulnerable to kryptonite because his weakness makes him human, and his strength despite it makes him a hero. Batman should continually wrestle with his parents' death because his pain is his power, and his emotional conflict makes him an everyman. Barbara Gordon should cope with paralysis because her intellect is her greatest weapon, and her enduring will to use it makes her a miracle.

Besides, DC asks readers to accept that a pair of glasses hides Clark Kent's alter ego from the world's greatest investigative reporter, who works beside him on a daily basis. Somehow, the Dark Knight's billion-dollar toys don't point Gotham's cops in the direction of the city's most famous billionaire. Simple eye-masks adequately safeguard other superheroes' secret identities, villains break out of maximum-security facilities every other week, and cities avoid bankruptcy from the real estate challenges, insurance premiums and repair costs of superhero-caused property damage. Suspension of disbelief comes with the territory in comic books, often being the very prerequisite that makes their stories work. And since Oracle's story has indeed been working for two decades now, singling out her cureless paralysis as "stretching credibility" more than any other plot-serving aspect of the DCU is problematic and uncomfortable in its own way.

Moreover, in a sense, Barbara's disability restores credibility to a universe rife with Mother Boxes that heal mortal wounds, White Lanterns that resurrect the dead, and cosmic Crises that rewrite history. The tragedy of Oracle's spinal cord injury tethers the DCU to a reality it often doesn't resemble, reflecting the danger, fragility and unfairness of real life even in the midst of the comics' zaniest sci-fi stints. If the numerous scientific and time-altering remedies that currently exist in DC comics were applied to every small fracture, serious affliction, or brutal fatality, its readers would neither feel the authenticity of suspense nor the cold bite of consequence. Barbara's paralysis is proof of the very real risks involved in the superhero lifestyle, forcing us to remember how courageous she was to put on a cape in the first place, and of course, how heroic she remains without one.

Between a wheelchair and wish fulfillment

The significance of honoring Oracle's disability thus far cannot be overemphasized, given that pop sci-fi tends to employ wheelchair users as characters to be fixed, rather than matter-of-fact mainstays of the norm. The dramatic power of the "healed paralytic" has popularity as ancient as the synoptic gospels and a draw difficult to resist for modern writers using super-science and the supernatural as conventional plot-pushers.

For example, the paralyzed Charles Xavier of the X-Men has walked multiple times due to cloning and magic. The leg amputee Flash Thompson, of Spider-Man's supporting cast, has new legs grown for him whenever he wears a symbiotic suit in the new Venom comic. John Locke, a fan-favorite character from the series Lost (2004), is a paraplegic who regains the use of his legs once he crash-lands on a mystical island. The moneymaking monolith Avatar (2010) is a film about wheelchair user Jake Sully, whose consciousness is stuffed into an able-bodied alien life form. Due to a transfusion of superhuman blood, Logan Cale of the series Dark Angel (2000) receives a temporary cure. Heidi Petrelli of the show Heroes (2006) is touched by a man with superpowers, which grants her the gift of walking. Perhaps most unsurprisingly, the comic-based show Birds of Prey (2002) features a faithfully rendered Barbara Gordon as the paralyzed Oracle, except for the "sub-neural" device she uses to give herself occasional mental control over her legs. Because these examples constitute only a portion of how often sci-fi characters shed their disabilities, it's apparent that the Oracle of the comics has been an extraordinary case—not simply because she uses a wheelchair in a sci-fi universe, but because she's managed to stay in one.

This wheelchair-discarding trend probably reflects the impatience and frustration of able-bodied writers toward paralysis, which are not, unto themselves, the "wrong" things to feel. It's a perfectly compassionate sentiment to dream of a future, or even a present, in which science finally breaks down the physical and psychological barriers thrust upon people with certain bodily limits. However, when addressing "liberations" from wheelchairs that frequent TV shows, films, and comics in the context of the cultural pity and condescension commonly directed at people with disabilities, it's worth considering whether the entertainment representing this population betrays the same "woe is them" attitude that society harbors. Interestingly enough, a majority of the characters above fail to make peace with using wheelchairs before standing up, creating a trend of paraplegics whose emotional completion lies in their cures, rather than their acceptance of circumstances.

And like those characters, DC's creators have apparently struggled with an indefinite obligation to the chair. The utterly unchangeable, challenging and sometimes maddening nature of paralysis has apparently worn down the publisher's resolve to play along with the permanence of the disability any longer (although this boiling point ironically provides insight as to how people adjusting to wheelchairs might feel every day, and why Oracle would be so important to many of them). Now, by using a free pass "out" that isn't available to people with disabilities and wasn't necessary for Oracle, DC is snubbing a minority group it desperately needed to remember in order to fulfill its promise of prioritized diversity.

Both more and "less" than her disability

Unfortunately, it's safe to say that several other minority groups would never have to suffer such a giant leap backward in DCU representation. Because DC Comics knows eliminating Barbara's paralysis doesn't have the same taboo as turning a black character white or a female character male, the publisher hasn't felt obligated to approach the issue with apology (or officially address the controversy at all). This is presumably because Barbara Gordon was introduced as able-bodied well before she became paralyzed, evidently earning DC the right to slant the change as a return to her roots instead of a slight to her disability.

Yet while it's true that Barbara's retooling would be a different matter if she had always been paraplegic, DC would be remiss to believe that the "lateness" of her disability stops it from carrying the same weight as race, gender, sexual orientation, or other characteristics known for inviting minority marginalization. Belatedly or from birth, people living with disabilities are often subject to the same discrimination regarding social equality, employment, housing, education, transportation, athletics, and so on. And it's doubtful, for instance, that a wheelchair-using fangirl wouldn't connect with Oracle for having a "recent" spinal cord injury over her own lifelong cerebral palsy. Rather, readers with varying types of disabilities have taken broader significance from Oracle through her fight for a sense of place and self-worth in an able-centric world. Among fans with disabilities, Oracle's paralysis has taken on more resonance than a superficial "condition" and become deeply and personally rooted in issues of identity.

The fact that DC is sacrificing this identity, essentially erasing the unique perspective and distinct emotional development that comes with it, is no longer a snag for Simone, who says that the regressive nature of the relaunch eased her mind about the moral messiness of having Barbara walk again:

"I could never really get behind, taking the Babs that's been running the Bat-verse, toppling countries, helping herd the JLA…putting that Babs back in the cape and cowl. I don't think I could ever have done that…. But now, everything has changed. If nearly everyone in the DCU, not just Batgirl but almost everyone, is now at a much earlier stage in their career, then my main objection no longer applies, because we are seeing Barbara at an earlier starting point." –Gail Simone to Newsarama

While this reasoning has some technical merit, its ethical value is still a tad lacking. To illustrate, it's highly unlikely that the same approach would be taken with DC Comics' famous Renee Montoya, a detective-turned-superhero who happens to be a lesbian. The character was introduced to comics in 1992 as a cop in Batman's city of Gotham, but it wasn't until 2003 that she was written as gay. Once Renee's sexuality was exposed, she was disowned by her parents, and found herself the target of malicious bigotry from colleagues in the Gotham City Police Department. In 2007, after a bout with alcoholism and a stretch of aimlessness, Renee gradually rediscovered her sense of purpose and later took up the superhero mantle of the Question, becoming one of DC's more prominent gay costumed crime-fighters.

If, hypothetically, the upcoming relaunch were to strip Renee of her Question persona, and return her to being the cop she was in her earliest conception, it's safe to assume DC would never re-designate her as heterosexual, the way she was originally presented. It's probable that DC would even refrain from placing her back in the closet, given what she's meant to fans as a hero taking the brunt of homophobia. Because Renee has already won devotees as an out and struggling lesbian, DC would have the sense to keep her that way, or risk deeply offending LGBT and straight readers who fervently value Renee's sexuality. While Renee is far more than her sexual orientation—and in fact wonderfully complex and fully idiosyncratic as an individual—her preference for women also intrinsically informs her feelings, her decisions, her desires and her sense of self. Annulling that part of her, even while it was an amendment to her original character, would be a disservice and disgrace to who she is now.

Much like Renee, Barbara was "separated" from mainstream society through circumstances beyond her control, profoundly affecting how she perceives herself and the world, as well as how the world perceives her. Like Renee, Barbara's new state has touched fans who relate to her frustrations or have been enlightened by them, with stories of her tenacity despite being looked down upon and underappreciated. And like Renee, Barbara is much, much more than what makes her "different," but because of that difference, also stands out as a beautiful and indispensable representation of something bigger than herself.

Driven bats over gender, race and class

The premise that the relaunch justifies, or necessitates, the reappearance of a pre-Oracle Barbara Gordon is also questionable, bearing in mind that the effects of the overhaul will not be uniformly applied to all characters:

"We have taken great care in maintaining continuity where most important, but fans will see a new approach to our storytelling. Some of the characters will have new origins, while others will undergo minor changes." –Bob Wayne on the relaunch

Evidence of Wayne's statement has shown up in DC's solicits for their September titles. Within the Batman "family" alone, three different characters that have graduated from the helper role of Robin are keeping their post-sidekick names and functions. Quite tellingly, two of those characters adopted their new personas 15-20 years after Oracle had adopted her own. Obviously, comic book creators have the freedom to make subjective and selective changes with any degree of impact they choose to best suit their purposes. DC, therefore, was no slave to any strict rules of their own relaunch, and certainly could have found a place for Oracle within the context of its revamped universe. Instead, DC used its freedom to "demote" Barbara from a niche she created for herself as a woman to a position she'd left behind her in girlhood.

Although Batgirl was never a sidekick, and Simone doesn't plan to make her one, numerous female fans of Barbara Gordon have expressed online that her regression is an unnecessary blow to her womanhood, especially since the adult males who were formerly Robins will retain their contemporary ranks and the maturity that they imply. Simone has confirmed that the name Batgirl will "make sense" to Barbara once she begins using it again, perhaps alluding to a de-aging of the character. Whatever the case, it's no surprise that DC's decision has had repercussions as a gender-based issue, bearing in mind that Barbara Gordon's greatest accomplishments as a crime-fighter and leader took place after her adolescence, while she was a woman in a position of rare power in the DCU.

Without a doubt, the name "Batgirl" has worth as it relates to empowering younger ladies, but two other characters in the DCU have adequately fulfilled that role in the wake of Barbara's retirement, and remain young enough to take it up again without needlessly tangling continuity. One of them is Cassandra Cain, an Asian-American heroine who brought the Batman books to a new frontier by being the first character of color to join the Bat-family. Just as when Barbara Gordon originally fought crime alongside Batman, Cassandra stepping up as Batgirl carried a great deal of social significance, and considering the mostly white characters that continue to dominate the DCU, that significance would still remain were she to reclaim the mantle.

The other character suitable for the role is Stephanie Brown, the current Batgirl, who took over after Cassandra's nine-year tenure in the cowl. Because Stephanie is a blonde-haired, blue-eyed white female, however, her replacement of Cassandra justifiably angered a great deal of readers concerned with the underrepresentation of people of color, and of Asian-Americans in particular, among DC superheroes. But despite lacking an ethnicity contributing to multiracialism in the Bat-family, Stephanie brings with her a working-class background that economically diversifies it. Since DC superheroes typically come from upper- and middle-class upbringings, continuing to use Stephanie as Batgirl might have at least somewhat supported DC's claim of redoubling its efforts on diversity. And though Simone has said that she might have a place for Stephanie and Cassandra in her Batgirl comic, she obviously won't be using either as the titular character any longer, and knows of no current plans to use them in any other book moving forward.

All in all, with the esteemed Batgirl title going back to the white, Middle American Barbara Gordon, in turn cutting off much-needed challenges to the racial and socioeconomic standards of DC's foremost superheroes, it's clear that premier disability representation isn't all that stands to be lost in the impending relaunch.

Simone's interview with a "real-life Oracle"

But it was indeed the loss of Barbara's disability that hit hardest for Jill Pantozzi, a writer for the comic book news site Newsarama who lives with Spinal Muscular Dystrophy. Because of her disorder, Pantozzi uses a wheelchair, and will likely have to depend on it for the rest of her life. Once she discovered that Barbara Gordon would soon become Batgirl again, she shared her emotional reaction via the op-ed ORACLE Is Stronger Than BATGIRL Will Ever Be, generating massive online support for her discontent with DC's decision. Her piece also drew the attention of Simone, who reached out to Pantozzi in an effort to extend her sympathy, set the record straight on some aspects of the change, and offer her perspective on the controversy with the interview Gail, Jill and Babs: A Conversation About BATGIRL & ORACLE.

Though abstaining from representing DC's head honchos during the talk, Simone did participate with considerable authority to speak on the situation, given her long history with Barbara Gordon. Simone's affection for Barbara, going back to childhood, has no doubt influenced the sensitivity with which she's approached Oracle for the years she's been writing Birds of Prey. Simone has followed in Yale and Ostrander's footsteps by portraying the character's bold confidence, unbelievable strength, and bottomless humanity from the wheelchair.

Beyond her management of Barbara, Simone is an appraised writer for DC Comics in general, as she is directly responsible for some of its bestselling work—and she deserves her own role model status as the only regular female writer currently on DC's staff. Further, Simone is responsible for starting the provocative site named Women in Refrigerators, a term she coined after a popular superhero's girlfriend was killed and stuffed in a fridge in a '90s era comic. The WiR discussion addressed how females in comics are commonly brutalized to advance male plotlines (The Killing Joke being a textbook example). So given her obvious aptitude for social consciousness, her accomplishments as a minority in the business, and her substantial experience writing for one in her comics, it's disappointing that Simone is now contributing to a brand of marginalization she's helped curb for so long. With her Barbara Gordon run to begin with Batgirl #1 in September, Simone will be using her sizable talent to work in the opposite direction of the progress and visibility she's provided Oracle.

However, despite fan outrage and Pantozzi's heartfelt op-ed, Simone carried herself with grace and the utmost sincerity during the interview, going so far as to tell Pantozzi that her bravery made her resemble a real-life Oracle. Along with her kind words, however, came rougher-edged truths, such as having to develop most of her justifications for Barbara's leg use after DC had already made the decision, and not the other way around. The fact that higher-ups moved forward without first consulting Simone, whose relationship with disability advocacy groups and readers with disabilities could have imparted invaluable insight on how to approach next steps, speaks volumes about DC's attitude on the situation. Even though Simone made it apparent during the interview that DC would have pulled the trigger on the new status quo with or without her involvement, Simone insists that DC "didn't take this lightly." Perhaps DC staff knew it couldn't take the aftermath of its Batgirl announcement lightly, but it's plain to see that it didn't treat the initial choice with much gravity or caution.

Its problems notwithstanding, Simone's own choice was certainly made more carefully, and during her interview, she makes a compelling point to support it:

"It's been sort of simply accepted that there's this block of disabled folks who are against this idea, en masse, and I do have to say quickly that that's not the case. There has always been a vocal minority of PWD [people with disabilities] who wanted to see Babs healed and out of the chair, always. It started out a tiny minority but it did get larger as the years went on. Again, I don't want those people to be forgotten. Even with some PWD advocacy groups, the response has always been mixed. I feel like I have to represent that group as well, here. It's a much smaller group, as far as I can tell, however." –Simone to Newsarama

While Simone conceded that this outlook isn't too widespread among fans with disabilities, her statement astutely deters inclinations amid DC's critics to speak for "the disabled community." Considering that readers without disabilities fall on either side of the Batgirl argument, it would be in poor taste to generalize and romanticize the opinions of those to whom the issue is most relevant. Further, there is certainly merit in contemplating the benefits of a walking Barbara for people with disabilities who have been hoping for it, perhaps starting with its potential for catharsis that able-bodied people could never fully appreciate. On the other hand, some readers may simply want to see their adored hero back in the "action," while happening to be fans with disabilities at the same time. In any case, Simone was on the ball to bring up an oft-ignored aspect of the debate, and it would do DC's critics well not to completely discount this opinion due to its proponents' low numbers.

That said, compared to their dissatisfied counterparts, people with disabilities who find joy in the prospect of fictional ability recovery never stood quite as much to lose in the Batgirl debate. As touched upon above, the physical restoration of characters with disabilities is a staple of sci-fi and comics, and won't be going away anytime soon. To provide more examples, Batman's paralysis was healed with help from a telekinetic metahuman, the Green Lantern John Stewart's paraplegic state was reversed with cosmic energy and psychotherapy, Iron Man's time as a paralytic was ended with an advanced microchip correcting his nervous system, and the list goes well on. In addition, the possibility of emotional satisfaction in seeing a beloved character stand up after 20 years may have short-term appeal, but not much by way of long-term significance. The cost of giving Oracle's "cure" moment to current readers with disabilities is that future ones would then grow up without her, and Oracle's rare and iconic status as an inspiration to people struggling with disabilities cannot be overstated. Having Barbara healed may encourage one present group of readers, but allowing her to stay in the wheelchair will encourage generations of them.

As for the call to "return" Barbara to the thick of battles with villains, it would be inaccurate to argue that Barbara has been so completely removed from it. Aside from the high-stakes, world-saving, and even adrenaline-inducing work she's done in a mental and virtual capacity from her wheelchair, the character has also used her extensive training in Eskrima—a Filipino martial art requiring a disciplined mastery of sticks—to contribute physically. With it, Barbara has been known to keep up with and defeat assailants when attacked, and because of it, Simone has even written Barbara on the frontlines of dangerous mission work. While of course Barbara has been participating in a more figurative fight than in her earlier days, she has still joined the literal fight when necessary.

Another issue that Simone addressed during her interview was creative overdependence on Oracle, because of the problems she's solved for other DCU characters:

"A lot of readers and a lot of editors had a story problem with Oracle, in that she made for such an easy, convenient story accelerator, that we missed the sense of having characters have to struggle to discover, to solve mysteries. Famously, it helped make Batman less of a detective and more of a monster hunter." –Simone to Newsarama

But as a blogger from ComicBuzz argued, the appropriate response to such a conflict would be to reform how the character is used, not to do away with the character completely. DC would never retire Superman because of the endless shortcuts his abilities potentially create for other superheroes. Instead, DC has written stories specific to the skills, styles, and suitabilities of its lesser-powered crime-fighters, and given autonomy to each of them during their solo adventures—even with their connection to an ally who could overcome most obstacles for them in seconds. Likewise, Oracle need not be undervalued for her value, but only used sparingly to keep other heroes' stories interesting, especially since readers have long enjoyed that their favorite characters brave challenges without dialing up their proximate deus ex machina. Simone hinted at understanding this later in the interview when she contended, "we never said there wouldn't be an Oracle." Her implication of a possible replacement discloses Simone's acknowledgement that Oracle's current function isn't inherently problematic, and could indeed continue to benefit the DCU with its one-of-a-kind story potential.

Because Simone obviously understands Oracle's worth in the DCU, it's puzzling to read her new attitude regarding the long-term potential of the character as is:

"As much as I love writing Oracle, and I do, I could write her forever…characters are not supposed to be preserved in amber. Even our favorite characters, ones that mean a lot to us…. And creatively, any writer will tell you, comfort is death in adventure fiction." – Simone to Newsarama

The "comfort" Simone refers to is stated in a context directly applicable to the relaunch, but not one entirely separate from the paralysis debate. As the rest of the quote definitively proves, Simone considers the wheelchair part of a familiarity that could keep Barbara static if clung to too stubbornly. While the spirit behind this mindset is sound, as it essentially demands that all creatures of fiction evolve, Simone directs her argument toward the very cause of Barbara's modern evolution, and one of the largest reasons Oracle remains fascinating.

Under Simone's direction, in fact, paralysis has continued to provide acclaimed mental and emotional development for Oracle. And in a universe that still features so few people with disabilities, Barbara's spinal injury remains one of the most innovative, original, and thought-provoking developments ever to happen to a comic book hero. The trailblazing quality of the character calls into question whether it's Barbara's paralysis that should be considered the "amber" in this situation, or the '60s version of her being revisited. If comfort is death in adventure fiction, then DC is oddly devoted to its most "comfortable" portrayal of Barbara Gordon.

Moving forward versus moving on

Surely, Simone has good intentions, but the road they pave isn't any less distressing. Ultimately, DC's decision to erase a dearly beloved character's paralysis has the same detrimental effect on fans with disabilities whether maliciously intended or not. And obviously, the recent outcry isn't from those readers alone, but also able-bodied fans that recognize the vital role of people with disabilities in our society and the urgent importance of their representation in fiction.

The function of people with disabilities in comics now is not only disproportionately small, but almost always comes with superpowers, mechanized enhancements or otherworldly fixes that render those disabilities a relative non-issue. In the DCU, Doctor Mid-Nite's blindness is countered with perfect night vision and the use of infrared lenses, the Red Arrow's amputated arm is replaced with a metal one, Freddy Freeman's limp is forgotten when he transforms into the physically superior Captain Marvel, Jr., and so on. These characters overwhelm the ones who reflect real-life people in more permanent circumstances, having about as much relevance as a black superhero gifted with the ability to "pass," or a gay superhero blessed with heterosexualizing super-tech.

Oracle, on the other hand, is one of the few characters whose disabilities have been treasured instead of negated over the years, and while a small amount of her true peers exist in comics, her equals simply don't at all. Barbara's resonance as a hero not in spite of—but because of—her limitations has never been matched. It's a shame that no character has earned anything close to the same sympathy, empathy, or celebration regarding disability issues, and while it's possible the future can bring some that eventually will, nixing Oracle is a backwards way to herald it.

Even still, readers shouldn't have to wait for adequate representation to resurface in Oracle's wake. Many with disabilities, and many without, are already waiting for a better fictional presence and portrayal of the population—and that's been with Oracle as an existing part of the DCU. In her interview with Pantozzi, Simone said that DC is "working" on the problem now that Oracle is on her way out. While bringing new attention to characters with disabilities is of course a welcome change, the timing of this effort is a wearisome indication of DC's attitude toward diversifying. A genuine interest in diversity would have spurred the publisher to action with Oracle still prominent in DC comics, not because she needs a spiritual successor or literal substitute. In truth, keeping Oracle and highlighting more characters with disabilities would have revealed an authentic concern at work rather than the turning cogs of tokenism.

While fans wait for DC to follow through on bringing in more heroes with disabilities, they'll have to presently settle for characters like Wendy Harris, the paralyzed caretaker of the Teen Titans superhero team, or perhaps Niles Caulder, a leg amputee of the Doom Patrol group (whose disability was recently nullified once he gained Superman's abilities—just before falling into his current coma).

But if DC gives them—or characters like them—more high-profile visibility down the line, hopefully the publisher will have the good sense not to make one of them the new Oracle. The last thing DC needs to insinuate is that there is only one useful role for heroes with disabilities in the DCU, or that even on a subtle level, characters with disabilities are interchangeable. Future representation should be as varied from Oracle as able-bodied people are from each other, and might even benefit from not going the "Barbara route" and involving superpowers, as long as those abilities don't undercut the gravity of the disabilities.

However, no matter how DC fares with possible future successes, the current dearth of DCU characters like Oracle has already swollen her emotional and ethical significance past a point of no return. It's easy to argue otherwise for able-bodied readers welcoming back the old Batgirl, many of whom won't ever know the sting of being unseen, unheard and "undone" as often in fiction as those with disabilities. Likewise, a great deal of DC's creators are able-bodied, and have the luxury of knowing that people like them will always be represented in the media they consume. With that in mind, DC cutting Oracle and standing by while Simone rationalized the decision was close to punching a stranger in the gut and letting a friend explain why it shouldn't hurt. As much as DC might not be taking this "lightly," most or all of its creative team will never truly grasp how it feels to be on the other side of this kind of marginalization.

A case often presented by able-bodied supporters of a walking Batgirl is that Barbara's treatment in The Killing Joke is sadistic, sexist, senseless (or all of the above), and because of its small part in the storyline, shouldn't have had repercussions so damning and unending. While their points may have validity, their aggravation toward the cruelty and haphazardness of the paralyzing event might help them understand a fraction of what some people with disabilities endure in reality. The emotions of those who weren't born with disabilities, but have had to deal with shock, rage, and feelings of powerlessness after the accidents that disabled them, are mirrored in the upset resulting from Barbara's misfortune. Moreover, even able-bodied fans' earnest hope for Barbara's cure might help them comprehend some of the needs and dreams of people with disabilities. Overall, Oracle is more than a reminder of a minority's existence in a world that forgets to consider it; she is also a catalyst for empathy among a majority that forgets to feel it.

What's more, Oracle normalizes having a disability by thriving outside the confines of Simone's "refrigerator," or victimhood—having long adjusted to her disability through hard work, self-assurance, and seeing life in her wheelchair as fully worth living. She's an indication of the capacity of others like her to succeed in the DCU without requiring cures to "defrost." In addition, Oracle's active part in her world, which unmistakably parallels the contributions of people with disabilities in our own, supports the notion that these kinds of characters should exist in the DCU without the constant threat of being retooled, rebooted or "rescued" from their situations.

Yet despite the importance of Oracle that DC has readily acknowledged in years past, the publisher now intends to let the character sit in back issue bins and trade paperbacks instead of interacting with the modern DCU community, demanding the significance she deserves. While DC has been open about attempting to achieve relevance through its revamp, its exclusion of Oracle clarifies that people with disabilities aren't immediately relevant to its new universe.

Of course, Oracle's disability isn't the only reason why she should matter in the revamped DCU. What that disability brought out of Barbara is also a precious piece of the character that stands to be lost. From a girl who was already determined, decent-natured and dynamic emerged a woman who endured the temptations of self-pity, escaped an envy of her younger self, and ended her thirst for vengeance against the Joker. Barbara used her paralysis as a means to forge a new freedom and focus to fight crime on a larger scale, proving that her disability didn't define her, and that she instead defined her disability—which was ultimately no hindrance to her passion, personality, or promise as a hero. As able-bodied advocates against her paralysis would agree, Barbara is infinitely more than her wheelchair. And because that's true, there are infinitely more aspects of her character to develop to make her a compelling fit in the new DCU.

Perhaps DC would do best to remember the underlying truth behind what's made Oracle work for more than 20 years, why fans are so upset about losing her, and where the phenomenon of disability pride comes from: Oracle has been a testament to the idea that people with disabilities don't essentially live lives less interesting, less meaningful, less "alive," or less complete than those without. Like Oracle, their role in society is different in some ways, the exact same in others, and crucial in either case. Oracle's revolutionary standing as a heroine who never needed bionic legs or a restorative redo to fit in has honored a group habitually hidden from sight, and emphasizes the import of not dressing "them" up to look like "us"—but rather recognizing the "us" in "them." Until now, DC Comics has rejoiced in the value of people with disabilities through a character that doesn't need to throw kicks to kick ass. But come September, the publisher will toss Barbara Gordon "back" into her role as a superhero, forgetting she's already redefined how to be one.

"She's fantastic because even just sitting in a chair in a dark room by herself, she's tremendously compelling. The DCU without her would be a much less interesting place." –Simone on Oracle, 2006

Visit the Barbara's Not Broken Facebook cause page to take a stand against DC's decision.

Photo courtesy of DC Comics. Originally posted at The Faster Times.