Posted in: Comics | Tagged: comic con, Comics, entertainment, howard chaykin, oregon, portland, wizard world, Wizard World Nashville

Howard Chaykin Entertains At Wizard World Nashville (Part 2)

By Cat Taylor

Howard Chaykin at Wizard World Comic-Con in Nashville, Tennessee: He had a lot of opinions and wasn't afraid to share them. (Part 2, find Part 1 here)

Since there was a larger crowd for Chaykin's second presentation, there were inevitably several parents with small children in attendance. He announced from the beginning that he would use foul language and suggested anyone leave who might get offended. He added, "I'm serious" several times and emphasized that he wasn't going to tone down his use of "bad words" just because children were present. Needless to say, he didn't disappoint and proceeded to decorate his lesson with statements such as, "Roy Lichtenstein stole work from people like Russ Heath and passed it off as his own without giving the real artists any credit. He was an elitist fuck!" Although Chaykin pulled no punches, most of his comments about other professionals were extremely complimentary, such as,

"Alex Toth informed the entire Gil Kane generation…John Severin never gets enough credit…Wally Wood could ink anyone's work and make it look incredible…and Mark Guggenheim is the most artist-friendly writer in comics because he understands how to call out shots."

All of this information eventually led to him dividing the entire comic-book genre into three narrative styles, asserting that,

"There are three basic strains of comic-book storytelling. There's Will Eisner who epitomizes emotion. There's Harvey Kurtzman who is about information. There's Stan Lee and Jack Kirby who represent impact.

Once Chaykin lunged into his official presentation, he started with a rapid-fire history lesson of comic-books from his personal perspective, which included such observations as,

"In the 1940s, most comics were drawn by teenagers awaiting the draft. So, most looked like crap. They created the comic-book language using the same tools that the newspaper comic-strip guys used, but that's really an entirely different medium and the structure used for comic strips isn't effective for an entire comic book."

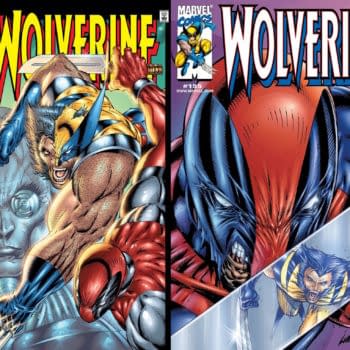

This was his way of explaining why the layout of comic-book panels needs to be different from the three-panel horizontal format of the comic strip. He basically said that a longer story continuing over several pages is an entirely different literary form and needs to be treated as such. He was much more complimentary of the comic-books of the early 1950s, but added that after the Comics Code took effect in 1954 they "turned them to crap." However, the decade he reserved for the most criticism was the 1990s.

"It was the worst decade in comics due to the excessive greed in the industry. It was personified by a group of men doing chicken-shit pastiches of the crap that made them rich."

Even though some of the attendees were unfamiliar with Chaykin's work, as some admitted, they soon learned that he wasn't just bluster but rather sees a certain psychology to the art-form of the comic-book narrative.

"Most civilians just think comics are disparate images on a page, and most comics today are scripted by writers who are illiterate to narrative form. They don't understand that there is an intentional form of communication in everything from the layout of the panels, to the space between the panels, to the way the images are drawn within that space."

He showed this by roughing out a five-panel layout on a large drawing pad in the front of the room. After completing his visual aide, he elaborated that he believes in the five-panel layout because trying to put more on the page "sucks the air out of the page," and further explained the purpose of each panel, from the initial horizontal "establishing shot," to the three-panels in the middle of the page, to the final image which should be a "return" or "callback" to the first panel. Chaykin went into great detail about the purpose and most effective use of the three-panel sequence, emphasizing that in our "culture of threes", the linear series of images represents a beginning, middle, and end. He also provided information such as,

"Panels in a sequence are typically the same size. If one is larger or smaller, that signals that something special or different is being communicated. The same can be said of the size or amount of detail of the characters drawn within the panels. It's an unconscious perception that readers have, and it should be leveraged by the artists."

In addition, Chaykin further detailed that even the space between the panels is important.

"The borders between the panels represent time. They give the story time to breathe and communicate how much time has passed from one image to the next."

Although he laid out his sample sketch to represent "the rules of the comic-book page", he clarified that there are many variations on the basics that still communicate the same information. For example, as he flipped over the paper of his sketchpad, he drew an entirely different five-panel layout that included several insets and a large three-quarter page image. He used this example to represent how his own personal style's evolution still preserves the critical narrative elements from his previous lesson.

Since this panel was a whirlwind of information in a short-span of time, it is unlikely that anyone was able to retain everything that was said. However, Chaykin summarized that,

"The three main takeaways from this presentation for any of you aspiring comic-book artists are first, the space on the page is a lot smaller than you think. Second, you have to make a narrative choice about what you are trying to say. Third, size matters."

Like he did in his previous panel, he concluded by serenading those of us in attendance. His acapella choice was "Big Bad Bill," which seemed to make him happy. Although I'm guessing that his mood would have soured if I told him I only know that song from an old Van Halen album.

Cat Taylor has been reading comics since the 1970s. Some of his favorite writers are Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, Peter Bagge, and Kurt Busiek. Prior to writing about comics, Taylor performed in punk rock bands and on the outlaw professional wrestling circuit. He has nothing in common with Wolverine except for being short and having hairy forearms. You can e-mail Cat at cizattaylor@hotmail.com.