Posted in: Comics, Recent Updates | Tagged: Comics, entertainment, First Second Books, Grey Williamson, Harlem Renaissance, Jabari Asim, Joe Illidge, Marcus Garvey, robert kirkman, Shawn Martinbrough, skybound, The Ren, Verge Entertainment, W.E.B Du Bois, Zane

Love, Crime, History And Art – Joseph Illidge Talks The Ren, A Tale of the Harlem Renaissance

By Nikolai Fomich

[The Ren]

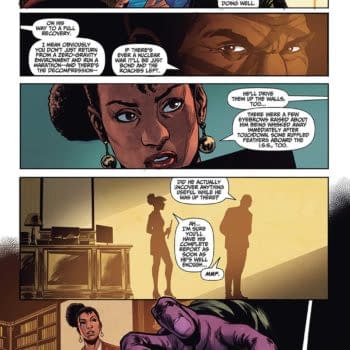

Continuing our conversation from earlier this week, writer, editor, and businessman Joseph Illidge and I spoke about the original graphic novel The Ren, co-written by Joe and Shawn Martinbrough (Thief of Thieves) and illustrated by Grey Williamson (Batman 80-Page Giant). The Ren is to be published by First Second Books and released in the 2015/2016 season. Set in the Harlem Renaissance, this noir tale tells the story of two artists falling in love during one of the greatest creative moments in American history.

Nikolai Fomich: Joe, what is The Ren?

Joe Illidge: The Ren is a historical graphic novel which takes place from 1925 to 1926. It centers around Clay Jackson, a young male bass player from Georgia, with dreams of hitting it big and becoming a successful musician. He doesn't think Georgia is big enough to handle his style, his energy. So, in a move which parallels the Great Migration of Black people in the early part of the twentieth century, he moves to Harlem. When he arrives, he meets Lisette Ford, a Harlem-born girl who wants to be a dancer – at a time when dancing was not really a viable career choice. Lisette's mother wants her to get into college and become a business woman like cosmetics entrepreneur Madame C.J. Walker, and while Lisette's at the top of her class, she's also an amazing dancer and wants to [pursue] that passion.

The Ren is about the romance between these two teenagers, during an amazingly creative time in Black history, and it takes place against the backdrop of the adult world of the Harlem Renaissance. The story involves visionaries and their philosophical conflicts (like the one between W. E. B. Du Bois and Marcus Garvey), the criminal underworld, and deals with growing up, with how the world can take some of the naiveté away from you.

[W. E. B. Du Bois]

NF: What were the origins of this project? What made you want to tell a story set during the Harlem Renaissance?

JI: Shawn Martinbrough and I talked about doing a young Black romance. That's something that I haven't seen in comics, and to this date – to my knowledge – it still hasn't appeared in comics. I can't think of a comic book with two young Black teenagers in love. If there is one, it escapes me. When we thought about that, we asked the question, "What would be the perfect setting for a story like that?"

Because Shawn's an artist and I'm a writer, we're both creative, so we wanted Lisette and Clay to be creative, artistic people. So the Harlem Renaissance, which was the apex of creativity for Black people in America – that was the perfect setting.

[Clay and Lisette Dancing]

NF: As a creator and as an African-American, what does the Harlem Renaissance mean to you?

JI: As a creator, it's really inspiring. You think you understand what something is, but once you start doing the research, you see the various layers behind it. For example, I didn't realize how much World War I affected the Harlem Renaissance until I did the research. Black men who fought for the United States believed they would come back and be treated with a sense of equality, because they served in the armed forces for this country. When they came back, they were still spat on, still treated like second class citizens, still denied certain rights. I didn't realize how that dissatisfaction, that disillusionment, was an element of the catalyst for the mentality that culminated in the New Negro Movement, which is what the Harlem Renaissance was originally called.

As an African-American, I feel that more of my people should know the wonderfully rich history of the Harlem Renaissance, its beauty and struggles. Black youngsters, especially – it seems like they're disconnected from the Civil Rights Movement, so I certainly think they're out of touch with the Harlem Renaissance. Doing a story like this can help make a contribution to graphic literature, and educate people. The Ren is not going to be a treatise on the Harlem Renaissance, but I hope it's going to be a story that once people close the book, they'll want to learn more – whether they go to Google, whether they go to their libraries, whether they go to Wikipedia. I would like it to be what comic book illustrator Jason Pearson once said to me, which is, I would like it to be a spark. It doesn't have to be the fire, just the igniting match.

I'm thrilled our publisher First Second Books has made it possible for me, Shawn Martinbrough, and illustrator Grey Williamson to tell this story. The opportunity for three Black men, all New York natives, all creative people, to tell this story about the Harlem Renaissance – it's an honor.

NF: Tell me a bit about the collaborative process between you, Shawn, and Grey. What was it like working with them on this project? What did you each bring to the table?

JI: It's interesting, because Shawn, who's known as an amazing artist – he's working on Thief of Thieves for Robert Kirkman's Skybound imprint at Image Comics – is also a big film fan. Anyone who knows Shawn knows how much he loves films, and he's developed a really good sense of structure, character arcs, and storytelling peaks and valleys. We were able to feed and vibe off of each other.

My background is that of a writer and editor, and so together we were able to mesh our ways of thinking and flesh out this story, which I view as a graphic novel in the truest sense of the word. The Ren is a novel with scope that is told in the sequential art format.

Grey was sought out by Shawn. His art has a very naturalistic look. There are a variety of different comic book art styles, and there are some people who can draw great superhero battles, but can't draw a compelling scene of, say, Clark Kent and Lois Lane sitting in a room having a conversation – which is just as rich and sometimes more dramatic than a superhero fight, if not more so. Grey has the ability to make regular life look interesting and be engaging. I love the cultural authenticity in his work.

[Joe Illidge]

NF: Research is obviously integral to historical fiction – including graphic fiction. What kind of research did you conduct for this project? And I know you already touched on this earlier, but what did you find most surprising and most fascinating in your findings?

JI: The first thing I did was visit Amazon and type in "Harlem Renaissance." I browsed through lots of book info, and then I went to Barnes and Noble – the one in New York City's Union Square, which is great. I went through a bunch of different books there and chose the ones that seemed to have the most information. I think on my first trip I bought four or five different books – on all kinds of subjects. I purchased a book on the history of Harlem real estate, and it turned out to be essential. Understanding how the real estate market worked in conjunction with Black people coming into the eastern cities as a result of the Great Migration – that's a part of the whole social ecosystem, the history lesson of Harlem.

I found a whole archive online of old copies of Crisis magazine, founded and edited by W. E. B. Du Bois, who was very influential in the Harlem Renaissance – and who also happens to appear in The Ren by the way. Giving a shout-out right here to Jabari Asim, the present E-I-C of Crisis, who pointed me in the right direction.

The most fascinating thing I learned…it would probably be part of the reason why the Harlem Renaissance ended. The Harlem Renaissance was significantly dependent on the patronage of wealthy Whites. When the Great Depression happened, that kind of patronage all but evaporated. The kind of people backing Zora Neale Hurston or Langston Hughes, they were no longer doing so, with significant consequences for many artists.

That's not something we deal with in the story, but it's relevant because there is a character in The Ren who has a somewhat prescient point of view.

NF: I'm guessing that position is going to be, "We can't rely upon white money to support our arts"?

JI: Yeah, his position is businesses should be circular, in that Black business should thrive off of Black patronage, and Black patronage should support Black businesses.

NF: The Ren takes place in what are arguably the two most important years of the Renaissance – 1925 and 1926. These years saw the assembling of extraordinary Black talent, men and women both racially and socially conscious, at the first two Opportunity magazine award banquets. 1925 saw the publication of Alain Locke's groundbreaking anthology The New Negro: An Interpretation, a consciously catalytic work which helped launch the careers of many of the Renaissance's superstars. How do the artistic protagonists of The Ren fit into this vibrant moment?

JI: All of them represent that drive to push and express oneself despite the different social obstacles confronting them. What the New Negro Movement spoke to was the overcoming of social and internal psychological obstacles – fighting the brainwashing of being told you're less than a person, of being told that you have to hold back. Asserting onerself as worthy of respect and possessing a unique greatness – that's what these characters are about.

NF: One of the stars of The Ren is Lawrence Denton, a former crime boss trying to go straight by investing in the future of young Black artists. How does Denton's thinking differ from that of the youngsters of his time? Other than artistic talent, what does Denton see in them that he himself may not possess?

JI: I can't reveal too much. What I will say about Denton is that, based upon his past experience, he knew the future had to involve a support of the arts in a way in which all people were welcome.

NF: The Ren is a love story – but it's also a noirish crime thriller. As a socially conscious creator, how did you juggle telling the crime story you wanted to tell but without playing into the harmful stereotypes about Black men as criminals prevalent throughout American media?

JI: The way I approached it was to explore the mentality of the entrepreneur. Looking at the origins of twentieth century crime – whether Irish, Italian, Jewish, or African-American – we're talking about a mentality focused on building foundations, for financial security and community empowerment. Crime happens on different levels, and there's a difference between selling booze and killing somebody. There's a difference between prostitution and killing. So I saw Denton's entrepreneurial background as a response to inequality.

All characters are human at their core. There's a reason why American society finds organized crime figures fascinating, even if their moral core deviates from ours.

[Walking Through Blood]

NF: I find it interesting that you were able to represent within The Ren so many different kinds of art – music, dance, and painting through your three main characters, and writing and illustration through your story's form as a graphic novel. Was that a conscious decision? Were there important reasons you chose these particular professions for your characters?

JI: It was a definite decision. We choose those professions because those were three of the biggest forms of artistic expression at the time. Though dance was not a viable career, it was definitely present at places like juke joints and was integral to Black life. It goes back to the hymns of the slaves. As a writer, it was important to keep in mind how these artists are different because of their respective talents. They each think differently, their body languages are different. Shawn's cinematic way of thinking inspired me to strengthen the script in this way. When Lisette is walking down the street, her posture, her energy – it's like a fireball is trying to get outside of her. She dances as she walks.

NF: As a jazz lover, I have to ask – will the Duke be making an appearance?

JI: [Laughs] I cannot say.

NF: Fair enough. Finally, what's next for you as a writer after The Ren?

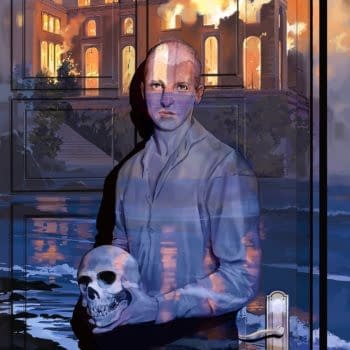

JI: I'm developing a project with New York Times bestselling author Zane for my company Verge Entertainment. With dozens of books under her belt, Zane is now the Publisher of Strebor Books, an imprint for Simon and Schuster, and her novel Addicted has been adapted into a film by Lionsgate to be released this October. She's an amazing co-collaborator, and our approaches to high-concept, character-driven drama dovetail pretty well.

[Zane]

My partners and I have been selective about how we're developing and releasing projects based on the Verge library of original ideas. The Ren with First Second Books is the first, with two other projects in development with established production companies, and the newest project with Zane.

I'll be making announcements on the various projects when the time is right.

Many thanks to Joe for taking the time to sit down and talk about this original graphic novel! Look for The Ren and more announcements about exciting projects from the creators at Verge Entertainment. Also check out our interview earlier this week: "A Career of Milestones – Joseph Illidge Talks Hardware, Batman, Diversity, And Verge Entertainment".

Nikolai Fomich is a freelance contributor to Bleeding Cool and college teacher. He is currently researching African history for his comic book series African Odyssey, about a time traveling history professor from Africa's future. Alas, he does not have a Kickstarter…yet.