Posted in: Comics, Recent Updates | Tagged: Ben Bolling, comic cons., Comics, cosplay, entertainment, fandom, It Happens at Comic-Con: Ethnographic Essays on a Pop Culture Phenomenon, Matthew J. Smith, McFarland Press, Ph.D., pop culture, sdcc

Exploring Comic Con Culture? There's A Book About That – The Bleeding Cool Interview With Matthew J. Smith And Ben Bolling

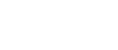

A few weeks ago, I interviewed Dr. Matthew J. Smith, a Professor in the Department of Communications at Wittenberg University in Ohio, about a field study course, "The Experience At Comic Con", that he runs at San Diego Comic-Con for college students, and it turns out that the course has already helped generate an academic essay collection edited by Dr. Smith and Ph.D. candidate Ben Bolling: It Happens at Comic-Con: Ethnographic Essays on a Pop Culture Phenomenon from McFarland Press.

Both Dr. Smith and Ben Bolling are Pop Culture scholars and authors with a deep interest in the phenomenon of comic cons, and developing a collection of essays is in many ways the first step toward bringing Pop Culture Studies to the attention of universities and starting to codify the many cultural aspects of fandom for future generations. Naturally, there is some resistance in academia to bringing Pop Culture courses into the college curriculum as well as biases (even from students!), and there are also challenges to gathering information about comic cons, but Smith and Bolling are undeterred. And they aren't alone. In collecting the materials for the book, they've demonstrated that there are many potential Pop Culture scholars out there, and it's a matter of providing the framework and encouragement for developing this field of study further.

I asked the co-editors quite a few questions about how they went about putting this book together, and also, given their interest and experience pertaining to comic cons, how they feel about the role of comics in con culture and where they think the explosive growth of cons is headed.

Hannah Means-Shannon: Why study Pop Culture? What difference do you think such studies will make to academia and to society in the future?

Ben Bolling: As someone who comes from a background in literary studies, I get that question a lot—and my gut response is: why would we not study the popular arts? Skills fundamental to literary studies—skills like close reading and contextual analysis—are not any less relevant in the 21st century. In fact, I find those abilities indispensible in an era we've dubbed the "information age." So the study of Pop Culture via literary studies requires a honing of those analytic skills to meet not only the challenges of new texts but also new kinds of texts. And the study of Pop Culture also opens up literary analysis to exciting interdisciplinary possibilities in fields like communication studies, fan studies, and sociology.

Matthew J. Smith: I've no fight to pick with anyone who teaches the classics. In fact, students should be exposed to artifacts that have passed the test of time and appreciate their impact on culture. At the same time, I believe that the academy is big enough to allow for and demand of us a critical perspective on the culture that we live in and are creating for our mutual engagement, not just the one we inherited from our predecessors.

HMS: What do you think are the biggest needs and/or challenges in Pop Culture scholarship right now?

MJS: The study of popular culture has never enjoyed as much interest or acceptance within the academy as it does currently; that said, such appreciation is far from universal, neither within the academy nor certainly beyond it. As dedicated scholars we have to continue to demonstrate that our methods are just as rigorous as those exercised by our colleagues who study "high" culture. If we observe identifiable standards about how we study popular culture, then we're likely to continue to win over some of the skeptics who question what we choose to study.

BB: Scholars of popular culture come from diverse academic backgrounds ranging from economics to art history, so the interdisciplinary conversations produced around pop culture scholarship are some of the most provocative and forward-thinking I've encountered. The challenge for current scholars working on the popular arts is to show through the quality and import of our work just how artificial and constricting the distinction between the "popular" and "the important stuff" really is.

[Ben Bolling with cosplayers as Wiccan and Hulkling at CCI 2012]

HMS: What do you pursue as topics in your own research? How do you conduct your research and what would you say have been your most surprising findings so far?

BB: I'm currently working on my dissertation at UNC-Chapel Hill. I focus on serials and the narrative strategies used to manage the histories of fictional worlds. So I'm interested in texts ranging from Faulkner's Yoknapatawpha narratives to Marvel's multiverse. I argue that analyzing the ways creators manage what we comics readers call "continuity" offers alternative ways of thinking about real world history. As a literary scholar, my research always comes back to textual analysis, but through Dr. Smith's field study at Comic-Con I've become increasingly interested in ethnography as it intersects literary studies. For instance, my essay "Queer Conversations" in It Happens at Comic-Con focuses on exchanges between LGBTIQ comics consumers and producers, their conversations about diversity in comics, and the perceived impacts these conversations have on the actual texts being produced. One of my findings I consider interesting if not entirely surprising is that through forums like letter columns, message boards, and conventions, comics fans have unprecedented means of directly impacting the creators of the texts they read if not the very texts themselves.

MJS: In addition to the ethnographic work I shepherd students through at Comic-Con, I'm very interested in the study of the auteur, or author, in comics. This tradition comes from film studies and focuses on how individual creativity leaves its mark on the medium. I've completed projects involving Alan Moore and Jack Kirby previously, and I've been consistently surprised by how the greats transcend the limitations of their medium—and the corporate structures that might otherwise suppress them—to make memorable contributions to the art form.

HMS: How did you select topics and chapters in It Happens At Comic-Con? Was it a matter of seeing what topics came in as proposals or were there certain areas you were hoping to include to give a wide enough cross-section of Pop Culture?

BB: One of the reasons why the Experience at Comic-Con had such an immense impact on my scholarship was that it exposed me to diverse disciplinary and critical perspectives for approaching the study of Popular Culture. So we were able to work with our contributors to select an array of essays representing not only different topics within Pop Culture, but different academic perspectives for approaching these topics, as well.

HMS: What's your advice to professors who would like to bring Pop Culture studies into the classroom? What sorts of courses would benefit from it or what dedicated courses would you suggest adding to the curriculum?

BB: Never approach Pop Culture studies without first addressing student biases toward the texts. One time I assigned the pilot episodes of Battlestar Galactica and American Horror Story in an American Studies course organized around the theme of "home." The juxtaposition of those texts with fiction by folks like Toni Morrison and Randall Kenan made perfect sense to me, but my students weren't buying it. Only after having a conversation about the expectations we attach to "popular" texts versus "literary" texts were we able to get down to the business of analysis. So I feel that any time I introduce elements of Pop Culture studies into the classroom, I first find it imperative to address the biases and expectations we bring to popular arts. And let me be clear, the tacit suggestion is that what is popular is "less than," "undemanding," "simplistic," "trashy," or just "bad." Only after we address those value judgments and the biases (from class to geopolitical) lurking behind them can we get down to the important work of analysis.

MJS: Ben's got the right idea. We cannot assume our students know or appreciate these texts on face value. We have to teach them just as we might a 15th century manuscript or 19th century novel. Besides, I find the process or "bracketing," or making the familiar seem strange, helps even the most ardent fans look at these artifacts more critically.

HMS: How can this book enlighten us about our own fan experiences?

MJS: In my own reading of these findings, I'm always impressed with two things. First, there is a sense of solidarity I find with my fellow fans, despite the difference in our passions. I don't have to be a Browncoat to appreciate what drives a Browncoat. Second, fans consistently demonstrate themselves to be smart people. There is a level of intelligence and self-awareness that they possess that runs counter to stereotypes of them as intellectually stunted.

BB: I couldn't agree more. I've found that after spending time with this collection of essays I'm more mindful of my behaviors as a fan and how I fit into a complex ecosystem of fandom. For instance, after reading Kane Anderson's essay on cosplay I've become much more attuned to my interactions with cosplayers at conventions. Why do I approach some folks to talk about their costumes and take pictures while only silently admiring the work of others? The essays in this collection all offer moments of reflection about our behaviors as individual fans and how those behaviors accrue to have macro effects on fan communities.

HMS: What part do comic cons play in the study of Pop Culture? Are they the be all and end all, or are there other areas we should also investigate and explore?

MJS: The fan experience, its rituals, rites, and rewards are only just beginning to be understood. Cons are exciting environments to explore these communities because they are so frenetic, but there are more and more avenues to do so. Back on campus I offer a semester-long course in "Cinephiles, Fanboys, and Geek Girls" where we can look at these other forums for community beyond the transient con.

HMS: What do you think are some of the causes of explosive growth in regional comic cons? Is this likely to continue or are there signs of "bubble" aspects to growth that may level out later?

MJS: I attend a number of the regional cons and even co-host a small, local one each fall (the Champion City Comic Con in Springfield, Ohio), and a common thread among them is the longing for connection and community I see demonstrated by the attendees. They seem to be seeking a communal experience that affirms their interest. The explosion of cons around the country is fascinating, and I'm especially interested to see how "mom and pop" non-profit cons fare against the more glitzy for-profit cons (like the various Wizard Worlds with their multi-media guests). I believe that the viability of the con scene will depend on the size and wealth of the fan community; the growth of the community will determine if the phenomenon is approaching a plateau, the edge of the bubble, or the dawn of even greater numbers.

BB: I agree with Matt that it's difficult to get a handle on where we are in the life cycle of comic con proliferation. Historically, I think we'll be able to see a correlation between the global financial crisis and consumer behaviors in the popular arts—but we may need a few decades perspective before we're able to make any claims beyond speculation. I'll also concur that the staying power of comic conventions seems to lie in their community-forging potential rather than purely consumerist motivations. I've been involved with NCComicon as a panel organizer for the last few years. The growth and success of that particular convention can clearly be attributed to the organizers' interest in fostering a community around the event, so that the event almost becomes a celebration of the community, itself.

HMS: What's the role of comics within wider Pop Culture in your opinion? Many people feel that comics are actually the "idea" breeding ground for films and animation, since they are cheaper to produce and spread to fans and then the best gets cherry picked for big budget development. Do you agree?

BB: We are certainly in a moment where properties, perhaps best exemplified by Marvel's growing cinematic/television/Netflix universe, have proven that ideas hatched in comics can translate into immense commercial successes. And in conversation with comics creators, almost everyone I've spoken to over the last five years has said that before the ink dried on their independent comics publishing deal, they had producers on the phone looking to snatch up film and television rights. So I do believe that comics offer a testing ground for ideas. But beyond that, comics as a medium seem to attract innovative storytellers—folks attuned to the possibilities of challenging traditional forms, of blurring the lines between visual art and written language. Ultimately, I believe that resonant ideas or stories rise to greater prominence in the cultural conversation. The fact that so many good ideas seem to originate in comics speaks not only to the talent of folks working in comics but also to the savviness of comics consumers who are often both early adopters and tastemakers in the larger cultural landscape.

MJS: For those of us who understand where Marvel's Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. or 300 originated, directing fans of the screen versions of these stories back to the comics from whence they originated is an imperative. Comics aren't sold in every drug store and corner market in the country anymore and if we want a vital industry to sustain itself and foster more great storytelling, I believe we have to introduce more readers to the medium. We are living in an unparalleled moment to do so.

Matthew J. Smith is a professor of communication and director of cinema studies at Wittenberg University, a liberal arts institution in Springfield, Ohio. Since 2007, he has led students across the country on "The Experience at Comic-Con," a field study where students examine the intersection of fan culture and marketing. In addition to his work with Ben Bolling on It Happens at Comic-Con, Smith is co-author of several additional books in collaboration with Dr. Randy Duncan of Henderson State University. These include The Power of Comics: History, Form and Culture (Continuum, 2009), which is a textbook for the comics studies classroom, Critical Approaches to Comics: Theories and Methods (Routledge, 2012), which was nominated for a Will Eisner Comic Industry Award for Best Educational/Academic Work, and Icons of the American Comic Book (ABC-CLIO, 2013). A second edition of The Power of Comics is due out this fall, a collaborative effort among Smith, Duncan, and comics legend Paul Levitz.

Ben Bolling is a Ph.D. candidate and Jacob K. Javits Fellow in the Department of English and Comparative Literature at the University of North Carolina- Chapel Hill. Along with Matthew J. Smith, he is the co-editor of It Happens at Comic-Con: Ethnographic Essays on a Pop Culture Phenomenon (McFarland, 2014). Bolling has also contributed essays to Comic Books and American Cultural History (Continuum, 2012) and Graphic Novels (EBSCO, 2012).

Hannah Means-Shannon is EIC at Bleeding Cool and @hannahmenzies on Twitter