Posted in: Comics, Recent Updates | Tagged: Boom! Entertainment, Comics, dc comics, Dynamite Entertainment, Effigy #1, entertainment, grant morrison, King: Flash Gordon #1, King: The Phantom #1, Munchkin #1, The Multiversity Guidebook, tim seeley, vertigo

Thor's Comic Review Column – Munchkin #1, Effigy #1, The Multiversity Guidebook, King: Flash Gordon #1, King: The Phantom #1

This week's reviews include:

Munchkin #1

Effigy #1

The Multiversity Guidebook #1

King: Flash Gordon #1

King: The Phantom #1

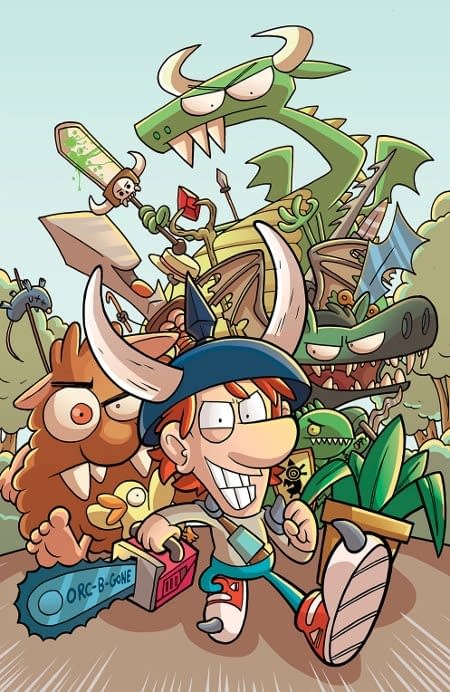

Munchkin #1 (BOOM! Box, $3.99)

By Graig Kent

Munchkin remains one of the biggest properties in tabletop gaming, an industry that continues to grow as playership expands, providing an in-person socially-engaging counter-measure to the cold and distant internet social networking. As massive and prevalent as Munchkin is, most of its prominence is a result of its games and expansions, as opposed to wildly branching out into multimedia and toys. The new Munchkin series from BOOM! Box is the first time the property has really branched out beyond gaming, and given the massive roster of races and classes and monsters the property is stacked with, there's a seemingly endless supply of tremendously fun stories it could spawn. With that in mind, Munchkin #1 is quite disappointing.

It turns out this new series, instead of being a joyfully silly adventure series is an anthology book, a slightly youth-focused humour magazine based around the property. The premier issue includes four shorts ranging from a single page to 13 pages. The first is an introduction: "What Is A Munchkin?". In a very obtuse way it spells out the basic sensibilities of the Munchkin game, highlighting the fact that it's goofy and fun with a sinister undercurrent. The second, "Humans Got No Class", takes half the book, finding a quartet of characters on a dungeon crawl, but the human character seems to be getting in the others' way. In the end the fourth wall is broken, revealing the fantasy was just that of players playing the game. The third once again presents characters on a dungeon crawl, highlighting the backstabby nature of the game (which each of the previous segments mentioned). The final one-page vignette, by game illustrator Kovalic, strives for a comic strip feel, but seems to be missing a joke.

It's a genuinely disappointing, largely inconsequential book that fails to deliver on all the promise of the property. The book spends too much time acknowledging the game and its rules without delivering stories that in any way engage on anything but the most superficial of levels. There's a tremendous opportunity here for entertainment but it utterly misses the mark. I enjoyed the cartooning efforts of Mike Holmes and Rian Sygh but it seemes like writers Tom Siddell and Jim Zub struggled with figuring out exactly what to do with the property in this anthology format. On the plus side, each issue features an exclusive Munchkin playing card, but then again for about the same price you can buy one of the collectible booster packs which has 15 cards in it.

Graig Kent plays games, reads comics, watches TV, goes to movies, raises kids and writes stuff about them from time to time. He also wrote a book, Quarter City, which is free to read on Wattpad.

Effigy #1 ($3.99, Vertigo)

By D.S. Randlett (@dsrandlett)

Where Grayson mingles superhero and spy genre tropes to achieve its goals, Effigy, looks to very different genre territory. The first is the obvious police procedural trappings. The main character is a former child star who shifted gears to policing when she moved back home after a career stallout. In terms of plot, there aren't too many surprises or upheavals of the first issue formula. There's a murder in a small town, and it's up to the local cops to solve it. What appeals about Seeley's script is his ability to use the solid plotting to exhibit some really great characterization and insight into modern celebrity culture.

While one can say that Effigy is about a murder and a character's attempt to solve it, so much of the story and setting is utterly steeped in modern celebrity worship. The main character, Chondra Jackson, used to be the star of a show (something like a mashup of Power Rangers and Lazytown) that probably aired on something like the Disney Channel. The evocation of Disney programming itself is important. More and more it seems like future celebrities are farmed on such children's programming. It is almost as if there is a certain media class composed of successive generations, wherein the stars you were patterned to love grow with you. If the are celebrity class years, then Chondra was probably voted most likely to succeed, except she never did.

And what's funny is that pretty much everyone from that media year is still stuck in that year except for Chondra. Among all the characters in the story, she herself is the one that has moved on the most from her old show and old career. It's people like her mother, or the mysterious prostitute who decorates her den with relics from Chondra's old show who have trouble moving on. Effigy hasn't gotten to a point where it can bring its themes full circle, but already it's using a compelling, if by the book, mystery to talk about a world where so much of our self worth is put into the media we consume and the toll that takes on the people who make it.

Marley Zarcone's art is a bit different than what we've come to expect from post Sean Philips and Eduardo Risso crime comics with its clean lines and bright colors, but it's absolutely perfect for capturing the feeling of the celebrity worship culture to envelopes these characters and their world.

Effigy boasts a very strong first issue. No wheels are reinvented, but the book presents its own compelling circumstances with a sense of humor and a keen eye for modern satire.

D.S. Randlett lives in the hills of Virginia and takes credit for the reviews that his emaciated twin brother writes while chained to the old radiator. He plays his guitar while biding his time for unsuspecting tourists and thinking about going to grad school.

The Multiversity Guidebook #1 Makes Me Want to Burn Things

By Adam X. Smith

So anyway…

As I'm reading this, the latest issue of Grant Morrison's long promised miniseries, I'm reminded of the article the late great Dwayne McDuffie wrote (and which Bob "MovieBob" Chipman in turn did a video about) where he discusses the possibility of what television programmes as a medium would look like if they took continuity anywhere near as seriously as comic books do. Certainly, with the likes of Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. and now Agent Carter straddling that line between print and visual media, there is more evidence than ever before that it is not impossible to do so, but the most consistent internal mythology in the world can't prevent people losing interest if the stories being told are flaccid or repetitive.

So I hope that you understand when I say that The Multiversity Guidebook is decent-to-adequate as a current potted history of DC Comics ala Secret Origins but bland and uninteresting as an actual comic, and that this wouldn't be a problem if at 80-pages it weren't an interminable slog to get through.

First of all, the framing story with the Batmen of Earths-17 (of the Atomic Knights) and -42 (Little League) and Kamandi the Last Boy, whilst not inherently bad, is spread so thin across the whole book that by the time we get back to them in the finale, we've forgotten what they were doing or why we should care in the first place. There's literally nothing to spoil because hardly anything goes on, more marking time until next month's issue and we get to see Uncle Sam and Nazi-Superman have a punch up.

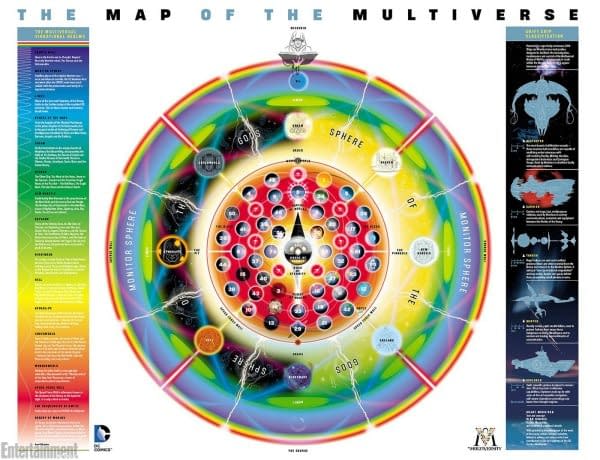

What that leaves us with is a 4-page rehash of the Crisis crossover concept with all of Morrison's little tweaks and idiosyncrasies woven in, a double-page spread showing the map of the Multiverse, and a 34-page index of all 52 canonical universes, including two thinly veiled piss-takes of Marvel's 616 and Ultimate universes. Except it's actually 45 universes on account of 7 of them remain unknown as some sort of heavily telegraphed plot twist, because it's not like we weren't spoiled for choice before when it came to actually telling a story with a beginning, middle and end.

Now, remember when I said that the Guidebook was at least marginally functional as a handy guide to Morrison's very particular vision of the Multiverse? Funny thing that. The map, for a start, does have the distinction of being relatively simple to understand whilst still giving us the notion of the Multiverse as a sort of discreet cosmic bubble with other realms like Heaven and Hell, New Genesis and Apokalips, the Underworld and even the Dreaming orbiting the 52 universes, so that the overall effect is somewhere between an astrological chart and the kabbalist Tree of Life. Where it gets a bit messy and annoying however is the fact that the central crease between the two pages squashes and obscures a lot of the details Morrison and designer Rian Hughes went to so much effort to include, and several of the captions and description boxes are not only teensy but riddled with typos. I don't usually mark a good book down on typos alone but the two combined together, along with the crease issue, makes the overall presentation of what's supposed to be this really important and detailed map look f*cking sloppy! Yes, I know it's an unfortunate side-effect of the way comics are designed and printed, but if the design doesn't work in that medium, you change it!

So anyway.

When we finally get to the Multiverse index, even with its stupid seven-world mystery box bullsh*t, it's pretty clear straightaway that Morrison, whilst still doing a commendable job cataloguing the various worlds and putting his own specific twist on them, hasn't created anywhere near as many of them from scratch as you'd think. In fact, aside from canonising Kingdom Come, Red Son, New Frontier and big chunks of the Bruce Timm animated canon as discreet universes – because Lord only knows we can't have them not be a legitimate aspect of the mythos to be used as a crutch whenever it suits the editorial team – it's pretty clear that after getting the really obvious ones out of the way, Morrison (or whoever's mandate he's following) quickly runs out of original ideas and the different universes all dissolve into a four-colour splurge of lazy tropes and archetypes, so that what we are presented with is less akin to a complex and dynamic mythos and more like a series of Futurama jokes or Family Guy cutaway gags.

"Oh, there's the cowboy universe. And the pirate universe. And the steampunk universe. And the chibi universe. And the one where all the heroes are black or distaff versions of their regular counterparts. And the one where John Constantine wears a cape and leotard for some reason." Ugh.

Our own Fearless Leader recently compared the Guidebook to Alan Moore and Kevin O'Neill's The Black Dossier, and superficially Morrison is clearly following a similar formula of framing world building meta within a larger A-plot. The difference is that The Black Dossier was a graphic novel-length book where the documents and artifacts contained in the in-universe Black Dossier had just as much attention to detail paid to them as the framing story, with the added benefit of each sequence being told in a different medium, with different narrative conventions and art styles each time – and it was all done by the same writer and artist throughout, creating a merging of universe and medium.

The Guidebook does an efficient job at explaining the mechanics and contents of the Multiverse and not a lot else, and while there are a dearth of artists who provide each Earth's description with a cool image of that Earth's heroes and villains, it doesn't really give you any indication of what that universe is really like beyond a thumbnail of the Earth, some prominent characters and a short textbox description, like the world's most boring museum tour decided to shake things up by throwing capes and masks on all the mannequins.

And yes, I know I'm playing directly to type by unfavourably comparing Morrison's work to Moore's for what must be the sixty-billionth goddamn time, but the fact is that if you open The Multiversity Handbook on a random page, you're not going to find an eclectic series of in-universe postcards, maps, journal entries, and excerpts from a reimagined Shakespeare play, a Jeeves and Wooster story featuring Lovecraftian monsters or a Nineteen Eighty-Four-themed Tijuana Bible, each with handwritten annotations in the margins – you're just not!

McDuffie and Moore both understood something about storytelling continuity that Morrison's miniseries seems to have entirely missed: what is or isn't part of the universe you create isn't what's important; it's what you do with it. The reason League of Extraordinary Gentlemen – and to use a non-comics example, the works of Kim Newman – inspire my unending and slightly overzealous loyalty is not about what characters get to play together in the sandbox, but the fact that the writers understand that, in the reader's imagination, there's no need for continuity – in the reader's mind, anything can be canon so long as it exists. There was a time when the DC universe was infinite, and McDuffie's Justice League: Crisis on Two Earths managed to parse that concept exceptionally in only a few lines of dialogue: in a more straightforward sense, the Multiverse is the result of people making billions of choices with billions of outcomes branching out ad infinitum. And whilst we may not have gotten our best use of it, for a long time, the idea that we could have as much or as little going on in the DC pantheon as we could imagine and the writers and artists could muster was enough for us.

So now, with the better part of 30 years of periodically rewriting the DC history books behind us and another massive continuity shakeup on the horizon, how do we find ourselves in a situation where we have 52 ongoing comics in circulation with barely a single interesting or unique story between them? Why do we find ourselves in a world where a 28-year-old insomniac bitching about modern DC comics being tin-eared and cynical is pretty much par for the course? Lord only knows, I don't enjoy being this jaded and pessimistic, and considering Morrison's apparent disdain for "gritty and realistic" comics, he's not really doing anything to convert me on whatever it is he's trying to sell.

To conclude, The Multiversity Guidebook is an oversized, overpriced appendix to a series that so far has promised big things that it has yet to deliver on, and whose only competent gesture is to act as 80 pages of free advertising for the rest of DC's back catalogue. Nothing that is contained in it is anything you couldn't find on a suitably detailed Wikipedia page and if its job was to sell me on any of the books that it's shamelessly plugging, it failed on that too. The book's single saving quality is that I now understand DC continuity a hell of a lot better than I did before or ever wanted to – it's a mess, an unnecessary obsession and a crutch used to avoid telling actual stories. You're not being taken on a magical adventure when you read this book – you're a guest at Disneyland being shuffled from place to place before you can see that all the children have measles.

Ladies and gentlemen, I've been Adam X. Smith. Please exit through the gift shop.

The Multiversity Guidebook: An Alternate (Universe) Opinion

By Graig Kent

Quite frankly (or Frank Quitely?), I loved The Multiversity Guidebook. Flat out loved it.

Even prior to this I've been charmed by the introduction to the Earth 20 Society of Super Heroes and I've been reminded what a tremendous property the Earth 5 Captain Marvel Family is when holding truer to its roots. I was utterly intrigued by the utopian Earth 16 where the bored offspring of yesteryear's champions engage in their little soap opera (though Adam may be right that it's possibly Morrison's cynical reaction to Millennials), and the Pax Americana Earth 4 was one of the most phenomenal storytelling exercises, Watchmen homages, and political conspiracy dramas in some time. So, yeah, I've been quite receptive in the Multiversity program, and thus am somewhat invested in it.

The purpose of the the Guidebook is two-fold. Foremost is laying out what exactly these 52 parallel Earths are, the second is to tie it into the overall storytelling framework of Morrison's Multiversity series. Whereas up until now each Multiversity story has been a done-in-one, mostly self-contained issue (with threads connecting it to the larger story), the framing sequence here is like Multiversity issue 1.5. You will at the very least need to have read the first Multiversity bookend, and probably even the Thunderworld issue to get the thrust of story being told here. At the same time, if you enter cold, you may find that you're getting a curious meta-tale that explores the DC Universe's vast history in a rather succinct fashion. As well, we get more involved with three other Earths (a Kirby mash-up of Kamandi and the New Gods on Earth 51, Earth 42 – a Tiny Titans/JL8-esque earth of cute superkids, and the Atomic Earth 17)

My colleague may not appreciate this, but what I've loved about Morrison's mainstream work, and what continually draws me to it, is his ability to embrace the forgotten (or even embarrassing) past and bring it back around into something useful again. Unlike Geoff Johns who fetishizes the past and in doing so often tosses away the present, Morrison brings it all together. Where Johns might disregard a part of history or break continuity in order to tell his story (sometimes for good, most times not), Morrison wants all stories to be valid, he wants all stories to be remembered, even the terribly silly or weird. Morrison respects what and who came before him. He's a fan, but he also doesn't dwell in his fandom, he still seeks to advance the story and the medium, playing with characters and storytelling conventions.

With Flashpoint and the New 52, Johns threw out the baby, the bathwater, and the whole tub, to try and start fresh. The results were at once incredibly successful (financially as well as drawing new readers in) and disastrous (the transition was alienating to a great many DC fans past, and for a good long while it seemed like nobody knew what they were doing). With a deceptively simple four-page, 16-panel layout, Morrison breaks down the history of the DC Multiverse, reincorporating into New 52 continuity elements of the past 55 years, ever since Barry Allen discovered how to get to Earth 2. For an old DC-head like myself, the simple acknowledgement that the stories I loved as a kid, a teen, and even an adult still count, they still have relevance…it means something, even if it doesn't necessarily play an active role in modern DCU storytelling.

One could say (and has) that Morrison does little but recycle the past, but I liken that to people who dismiss the artistry of DJing. Morrison, like, say, DJ Shadow, uses and reshapes bits and pieces of the past to make something new and original. And like Shadow, Morrison doesn't just manipulate the past to fake something new, he always, always adds something new, something of his own to it, otherwise what is the point beyond superficial entertainment.

Which brings us to the breakdown of the 52 Earths. Here we have, across 33 pages, pin-ups and a one-paragraph breakdown of each Earth. The breakdown for each Earth is slight, I have to concur, but it does effectively differentiate each Earth from one another. To have too much text, to lay out too much of what each Earth is, would be to constrict that Earth and its storytelling possibilities. Likewise, Adam X points to the seven unknown worlds as a failing of the book, whereas I believe it's purposefully leaving a few slots open so others can generate new worlds and add to it. This isn't all Morrison's show. The dedication written on "The Map of the Multiverse" ("With the grateful acknowledgement of the work of the many artists, writers, colorists, letterers, editors and others who have contributed to the rich tapestry of the DC Comics Multiverse") is perhaps the simplest explanation of what Morrison is doing here, which is just bring a little bit of logic and order to 80 years of world/universe/multiverse-building, while still building it out even further.

[*Side note on the generally astounding Map, which is the same one that has been in distribution since San Diego last year: Adam X is correct that, especially after all this time, those typos are inexcusable.]

The 52 Earths, as laid out here by Morrison, are yet another chapter in his long love letter to the malleable DCU. Earth 9 takes us back to the Tangent universe, while Warth 11 brings back Barbara Kesel's Elseworld's Finest world where most of the major superheroes are women, and Earth 12 is that of Batman Beyond's (which by proxy also means the TV Justice League Unlimited, also noting that Earth 50 is that of the Justice Lords, the TV JLU's alternate Earth). Earth 18 is a combination of the Justice Riders Elseworlds [with early J.H. Williams art, worth seeking out — ed.] and DC's old west comics, Earth 21 is Darwyn Cookes' New Frontier, 22 is Kingdom Come, 26 is Captain Carrot, 39 is a T.H.U.N.D.E.R. Agents analog (likely this was originally supposed to be the actual T-Agents back when Morrison first started Multiversity and DC had the license), and 43 is the vampire earth from yet another Elseworlds, Red Rain. Think of this New 52 as a bit of a Morrison-curated DC Universe museum, and there's a sense in Morrison's framing story that any of these Earths could be swapped out for another if the creative of Earth 33 or the Monitors so desired it. It's a lovely framework for DC's house, but the interior design isn't set in stone.

I was 10 when I discovered DC's Who's Who in the DC Universe, a 26-issue series that was essentially an encyclopedia of most major and minor DC characters in DC's then 50-year history. As a kid I poured overed those pages, learning all about the histories and powers of some heroes and villains I to this day have never otherwise seen in action on the page. While the Multiversity Guidebook doesn't have quite the same depth, I received the exact same charge while reading this, turning each page to discover what the next Earth contains, sensing both the familiarity and the differences. Like with Who's Who, the Guidebook sets my imagination a-runnin', and puts a big dumb smile on my face as I consider the possibilities. In these Earths there contains both the memories of past enjoyments and the potential for so much more to come.

I've been harsh on the New 52 but I've seen the turnaround in recent months, the relaxing of editorial, the liberties and trust given to creative that should have been there from the beginning, the actual practice of telling new and different stories, not just the hype. The Multiversity Guidebook fits nicely into this turnaround, building a structure for the DC Multiverse going forward but not totally hindered by detail and minutiae.

A final note of credit to Marcus To (colours by Dave McCaig) who nimbly genre-smashes the world of the Little League and the Atomic Knights (and all those multiverse Sivanas) as to make it nicely all gel together. Likewise credit goes to Paolo Siqueria (colours by Hi-Fi) and his gorgeous, feathery, Kubert-esque handling of the Kirby-world, bringing the New Gods, Omac, and Kamandi into the same space beautifully without somehow aping the King at all. And both artists negotiate the meta story, as they become aware of the concept of the Multiverse through discarded comic books and cave drawings with genuine zeal. I would love to see both work with Morrison again.

Yeah, I loved it. I've read it twice over and I'm going in for a third. If anything, I'm sad there's only 52 Earths, I could totally do with another 52 more. At $7.99 your mileage may vary, but I got more than my money's worth.

Graig Kent wrote another review in this column. You can find it by scrolling up.

King: Flash Gordon #1 and King: The Phantom #1 (Dynamite)

By Jeb D.

Which, let's face it, is also a pretty good description of work-for-hire in the world of Corporate Superhero Comics, but that doesn't stop me reading Daredevil.

So, let's put preconceived notions aside for a moment, and consider these two latest offerings from the King Syndicate intellectual property catalog; I'm guessing that both lead out of the Kings Watch series, which I haven't read, but presumably these should be able to stand on their own.

It would seem natural to pair Thrilling Adventure Hour creators Ben Acker and Ben Blacker with Flash Gordon, given that the version of the property most familiar to today's readers was an over-the-top cheesefest graced with the presence of Brian Blessed's wings, Timothy Dalton's mustache, Freddie Mercury's bandmates, Max Von Sydow's leer, and Ornella Muti's bondage-prone catsuit. But I've always found Thrilling Adventure Hour more vaguely amusing than downright funny: the old-time radio tropes they trade in have been grist for the comic mill for half a century, from Bob and Ray to the Firesign Theatre—hell, to Garrison Keillor for that matter. Here, as with TAH, there's a sense that Acker and Blacker work as though they're breaking new ground in deconstruction; but the juxtaposition of hoary space-opera clichés with modern sensibilities is practically its own genre these days (see Graig's recent review of Galaxy Quest, among other things). The laughs in the Flash Gordon film come from everyone playing it straight; the laughs here are intended to come from everyone playing it off-center, and the pleasures are milder.

Character archetypes are naturally tweaked for contemporary sensibilities: Flash shows us how the typical "hero" role tends to the impulsive and headstrong, and Zarkov's Stark-like techno genius is as sly and smug as Larry Ellison. Dale Arden's characterization is trickier. The attempt to take her out of a conventional "damsel in distress" role is all well and good, but I'm not sure it gives her any more agency, because her character still expresses herself solely in relation to Flash: instead of a helpless female waiting to be rescued, she's simply a wisecrack machine rolling her eyes at Flash's lunkheaded machismo. And while there's nothing wrong with Dale tossing cold water on Flash's horndog tendencies with a contemporary-sounding bit of snark ("Babe? NOT OKAY."), just the fact of it being modern isn't sufficient: it needs to be in some way unique or witty, or it's no more use to us than cornball dialogue out of a Republic serial. It often feels as though Acker and Blacker are going for a sort of shaggy "Hawkeye in space," here, but without the foundation of the Marvel Universe to give it resonance.

The art from Lee Ferguson is exemplary: rather than emulating the lushness of classic Alex Raymond (see: Gorlan Parlov's Starlight), he seems to take the scrappiness of 60's-era Gold Key as his starting point, but injecting more life and characterization. The stark backgrounds may leave the book feeling a bit underpopulated, but the no- nonsense paneling and sharp, well-defined figure work keep the eye focused on the storytelling.

I don't want to come down too hard on Flash Gordon: it's a nice bit of breezy fun. When the current contract ends, and these characters find themselves in other hands down the road, this series is unlikely to stick in the collective memory as do Alex Raymond or Sam Jones, but as the Flash Gordon of record for 2015, we could do a lot worse.

Of course, it can be argued that Lothar's being black doesn't necessarily make him more worthy of the role than the Walker family's centuries in Africa make them, but there's no question, if we're to have a Phantom, a version of the character that gets away from being a White Savior on the Dark Continent is a nice change of pace. And given that, as with Flash Gordon, changes to The Phantom will inevitably be brushed aside when the property is surrendered to another publisher in the future, Clevinger could afford to take the tack of eventually settling the mantle on Lothar in an official sense.

Lothar's not our sole protagonist here, and that's a bit awkward: early in the story, we're introduced to "Ace reporter Jen Harris, following some money from New York to India, Indonesia, and now to East Africa." Problem is twofold: 1. Jen Harris is a sort of updated white savior (though a female one) and 2. That's actually her first-person narration. It's a shame that Harris' role is so "tell-not-show," because some of Clevinger's dialog in this issue crackles with a nice, dry wit, which makes the clunkier exposition stand out. It's also a little disquieting when The Phantom takes out a pair of baddies by shooting them at close range, then casually responding to their cries of pain with "Oh, hush—y'got body armor;" it's a cartoony bit that feels out of place in a story that's trying to place itself within a more or less "real world" environment.

Also clumsy is the backstory that was, presumably, set up in Kings Watch: the brief introductory page tells us that a repulsed alien invasion "knocked our technology back one hundred years!" At first, I thought that the somewhat overly-specific time reference meant that the invasion took place during the early 20th-century newspaper strip era that originally birthed characters like Mandrake and The Phantom, giving Earth 170 or so years to get caught back up. But the not-much-past-her-teens Harris laments that there's no more Internet, though she indicates that she'd used it as a reporter, which places the event within just the past few years, with no real explanation as to why the technology seems functional and recognizable (among other things, she has a cellphone), and suggesting that the backstory has no real purpose beyond making it impossible for people to google everything; otherwise, there's not much to suggest that this is not our 21st century. I shouldn't be surprised if this is explained in Kings Watch, but if we're still running the "every comic is someone's first" playbook at this late date, it would be nice if the explanation were better integrated here.

Lothar's quest for the Walker scion will involve gaining the trust of the usual group of ruthless white mercenaries, abetted by his young, black hipster factotum/tech guy; their banter ranges from the obvious to the painful. Though the mercs are a fairly generic group, Clevinger manages some amusing interchanges between their leader, his men, and Harris. The issue ends on a fairly predictable cliffhanger, but given the amount of spadework that went into setting up Lothar's cover as bodyguard to a warlord named "King Guillotine" ("Good name," remarks the head merc), I'm guessing the good guys are talking, not shooting, their way out of it.

Brent Schoonover's art is clean and clear, with good, if sometimes inconsistent, facial characterization, and backgrounds that feel appropriately lived-in, thanks in large part to outstanding color work from Robt [sic] Snyder. Not a ton of action this time out, and what we do get is a bit stiff.

(I'm also amused by the fact that having his face appear in exactly one panel gives Mandrake The Magician a big "Guest Starring" callout on the cover: I'd call it "bait and switch" if I was convinced there were actually Mandrake fans out there to be baited).

Of the two comics, The Phantom is obviously the one taking the chances and breaking new ground, with its twist on the property's cultural/racial history, temporary though it may prove; on balance, though, I think I'd give a very slight edge to Flash Gordon's po-mo space opera, as much for its briskly vigorous art as anything else.

Jeb D. endures Silicon Valley traffic just to go get comics to review for you. He feels the love in return.