Posted in: Comics, Recent Updates | Tagged: annihilator, batman inc, Comics, dc comics, entertainment, grant morrison, Legendary Entertainment, multiversity

Grant Morrison Comics: What If There's No Secret Message?

By Nas Hoosen

I remember an article about Batman #655, Grant Morrison's first issue of what would become his seven-year Batman run, from around the time that issue hit shelves. I can't remember who published it anymore but one thing I do recall is its author's obsessive examination of that first issue for layers of hidden meaning. While the article obsessed over the thematic resonance of Jim Gordon's fall down Page 1, it paid very little attention to the weird bit of graffiti that would come up again as probably the most significant thing in that first leg of Morrison's run on Batman. If ever there was an indictment of how obsessive we superhero comic fans are, I think it was a reviewer glossing over something that was actually there to be considered and dissected in favor of exploring a metaphor that ended up having little meaning in the grand scheme of the longer story.

Of course, Grant Morrison's work has inspired this kind of devotion from readers for years, and with good reason. I often revisit his work and find I come away with new understanding, even from the stuff I've read a dozen times. The guy punches holes in his own plots and teases out information with stray lines of dialogue like no one else. His stories present a constant "hole in things" for readers to obsess over like each of us is the World's Greatest Detective.

Here at Bleeding Cool, that obsession has even prompted one contributor to examine Morrison's earlier works, despite his dislike of the author's work. It seems that Morrison's persona is so divisive that non-fans are willing to purchase his back catalogue, even if its just to complain about it.

Of course examining the man's work is all well and good, and usually a lot of fun, but I think it's also telling that many fans do so with such poe-faced seriousness that they miss one of my favorite things about his work: the jokes.

While he hasn't hesitated to depress readers in the past, it's usually been in the service of pointing out the inherent absurdity in everyday human behavior. This is the guy, after all, who had Darkseid possess 3 billion human beings by getting them to give into despair through the internet. That's a touch of commentary on global culture by way of an almost incidental beat in a story about a dark god dragging all of existence into the endless hell inside himself. If you can't tell from that one line summary, Final Crisis may not be subtle but its subject matter involves some pretty heavy social commentary.

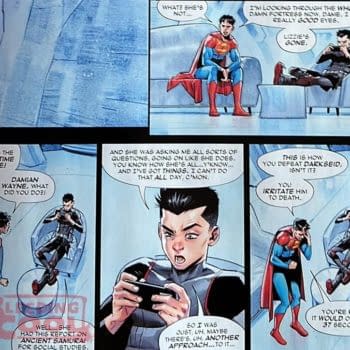

Now Morrison's always displayed a sense of humor in his work, sure, but I don't think it's ever been so consistently prevalent as it's become in recent years. While there's a lot of sadness at the heart of his Batman run for example, Batman Incorporated wraps up with a woman putting Batman in his place by shooting the crazy ex he ignored for years in the head, then leaving him standing alone in his cave with his pets. It read like a put-down of many straight white male comic fans' (and perhaps DC itself's) possessive attempts to keep Batman the way he was in the 80s, when the comics industry first "grew up".

Multiversity has pushed things to an even more absurd place, with Cthulhu-esque villains who drain characters dry while refusing to let them die, all condensed into their rather silly mission statement: "WE WANT 2 MAKE U LYK US" (emphasis mine). That's in a book where the breakout character is a cartoon rabbit who makes a point of yelling about the significance of cartoon physics.

My point is, Morrison's never been a subtle guy, but before his work tended to be quite straight-faced about encouraging superhero fans to grow up and enjoy their favorite characters. These days he seems to have dropped that approach in favor of just outright laughing at us, and I think it's absolutely fantastic.

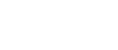

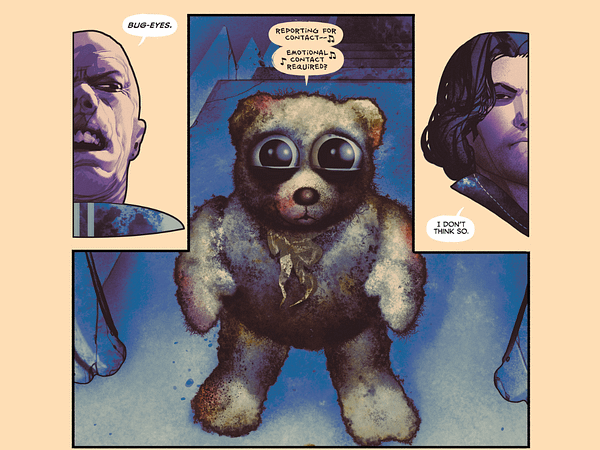

This brings me to Annihilator. It's only been out a few hours at the time of writing and already reviews are pointing out the obviousness of some of its symbolism, or the broad strokes Morrison uses to communicate character and theme. There's been some mention of how dark and depressing the central conceit about the black hole is, but to be honest, the book doesn't seem as concerned with all that as readers may be. If anything, it reads like dark comedy, and that means Morrison's usual statements about the connectivity between our imagination and reality isn't anywhere near as important as the way it's poking fun at the Hollywood studio system that's currently making superheroes "real" for a much larger audience than comic fans.

It's got some people thinking, sure, but the black hole at the center of a neurotic writer's skull that may or may not have spat a real-life Byronic trickster anti-hero into his house seems almost intentionally quaint. At this stage, it looks more like Morrison knows we'll pore over his work obsessively regardless of what it all means. That's not to say it doesn't mean anything, but that what its saying may be right there on the surface this time, attempting to draw our attention to the seriousness of our search for meaning in fiction by getting us to laugh at ourselves. Maybe we're all Nix Uotan, trying to dissect "haunted" comics in search of some deeper meaning, and we're missing the message that's right there because of it.

Or, I suppose, I could just be seeing my own secret meaning in all this. Drat.

Nas Hoosen is the co-founder of Another-Day, South Africa's Least Favorite Website About All Its Favorite Things. Sometimes he still has 'Nam style flashbacks to his time spent working the counter at the local comic shop.