Posted in: Comics | Tagged: Comics, sharon moody

In Defense Of Sharon Moody

Dean Butters writes for Bleeding Cool;

In defense of appropriation and Sharon Moody (who I have never met or even heard of until the article on Bleeding Cool)

When I first read Scott Edelman's article about Sharon Moody's work, I was disappointed. While undeniably passionate about comics, Edelman seemed oblivious to the history of appropriation art, and it would seem, missed the whole point of Moody's work. Edelman chose very quickly to dismiss rather than engage, this reaction reminded me of those occasions when Rich pulls an article off Fox News, or some similar right leaning site, about a comic book story that has exploded into the mainstream media. Superman renouncing his American citizenship and Captain America fighting the Tea Party being two good examples of this. When reading these articles I imagine a number of Bleeding Cool readers, like me, are horrified and dumb struck by some of the things written. In the end however, we sit back and look down on these people because they are writing about things that they have not bothered to look into, because they are ignorant of the traditions and contexts in which these comic book stories have occurred.

They choose this ignorance and indignation over bothering to educate themselves, because it is far easier to attack something that you don't understand than to engage with it and learn about it. It was for this reason that I was disappointed in the article, and asked Rich for the opportunity to write a rebuttal.

From the outset I'll declare my bias: I and a number of my friends are artist, and some of us do use appropriation within our work. Edelman's complaint seems primarily directed at the appropriation of another person's work without attribution, and the accuracy of said appropriation. The whole article is however written as if the well-established tradition of appropriation art was not so, shall we say: well-established. Appropriation is as acceptable a form of art making. as inking is to the production of comics. Calling appropriation art plagiarism is like someone who dose not understand comics calling an inker merely a 'tracer.' Having said this, I will not deny that appropriation works are not at times contentious and that their artist are sometimes embroiled in legal battles.

Appropriation works are about transforming the way we think about things, about recontextualizing the appropriated image as a way of offering comment on the source, society, the media or what ever else the artist seeks to make comment on, about questioning ideas of authorship and asking the viewer to reexamine their ideas about the world.

While not the originators of the idea, 1960's pop art was littered with appropriations. Warhol's Campbells' Soup cans and Brillo Boxes took the imagery of mass culture and embraced it just as America embraced these things. Warhol's Death and Disaster series and many of his celebrity works were taken directly from press and publicity photos.

Richard Prince regularly uses appropriation in his work, probably the most famous being his Cowboy series, where Prince rephotographed Marlboro cigarette advertising, reframing and composing the images. The work sort to address ideas of American masculinity and the nature of what is real. Prince's Nurse Paintings were taken from the covers of pulp romance novels, the covers were scanned and then printed onto canvas, at which point much of the background and image was painted over by Prince.

Sherrie Levine created exact reproductions of Walker Evans' work for her show After Walker Evans where she rephotographed images from the exhibition catalog of his show First and Last, presenting the work as her own. Not only did the work seek to question ideas of Authorship, originality and the commodification of art, but sort to present a feminist usurping of patriarchal authority. Now I am sure some of you will read that last sentence and think that 'that's just art wank,' but it was the 1980s and feminist dialogs were a driving influence on the photography of the time.

I do agree with Edelman's point that unless you are well versed in comics you will not know the names of the artists that Moody is appropriating. I however disagree with the assumption that the intended buyer would assume these images 'sprang whole from the mind of the artist'.

This assumption seems confounded by the implication that Moody has produced a series of works that solely 'plagiarise' comic books. However, a quick visit to Moody's website will reveal that the artist has a whole series of works in this style. The assumption that the uninformed viewer will see this work and believe that this comic book imagery is solely the creation of Moody, is simply erroneous. It is obvious to even the casual arts observer that Moody is painting objects. Indeed, for this assumption to hold water it would also have to hold that this casual observer would similarly attribute the creation of the Hershey Bar, the US one dollar bill, and the child's cowboy guns, among other things, to Moody. As this is not the case, why then would one assume that, a portion of Moody's work, this comic book art, is entirely Moody's creation. The answer is that one would not.

I wade into this next paragraph by first saying that I am by no means a lawyer, so I am going to tread lightly here. Nonetheless, in legal terms, fine art sits in a different space to commercial art. Firstly selling an artwork in a Manhattan gallery, even if one sells it for a lot of money, does not make it 'commercial art,' or a commercial infringement of copyright. I will use a photographic example here to talk about the difference between artistic and commercial exploitation. If you are taking someone's photo to sell a product, you need a model release, because this is a commercial exploitation. If you do not have that contract, and you are using someone's image to sell your product, they are well within their legal rights to sue you for doing so. If however you take someone's photo as an artwork, you do not need a release. Indeed, if a photographer is taking a photo in a public place they don't even have to tell the person you have taken it, or sought their permission.

The photographer, Philip-Lorca diCorcia, was sued by Ermo Nussenzweig, who objected to diCorcia photographing him on the street, and exhibiting that work. The lawsuit was eventually dismissed because the work was art, not commerce, and thus protected by the first amendment. The judge ruled that even though ten prints were sold for between $20,000 and $30,000 each, this did not mitigates the works position as non-commercial, or diminish its artistic character.

I would also be reasonably confident here in suggesting that legally, comic book art, because of the work-for-hire nature of the contracts that the artists sign, would not be considered 'art,' legally it would be viewed as 'commercial art.' I don't say this to diminish comic book art in anyway, I love it, I think it is brilliant, but when you are using words in legal terms they mean different things than in every day language. In Rich's follow up article, Vartanoff is making a legal argument and she is using word commercial incorrectly and thus most of her assumptions don't hold (though she is correct about the need to vigorously defend copyright from commercial exploitation).

Despite the important history of appropriation within art, copyright issues are becoming more common. Hirst was sued over the Hymn work, Prince is currently appealing a copyright ruling in relation to his Canal Zone series and Koons has both won and lost a case on the grounds of 'fair use' within copyright law. I would suggest that this is reflective of the increasingly litigious society we live in, and progressively restrictive changes to copyright law driven by corporations. However, while it may at times prove a legally contentious issue, this does not reduce the legitimate practice of appropriation within art.

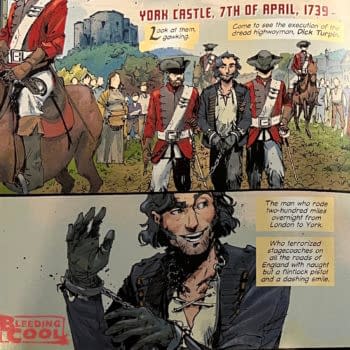

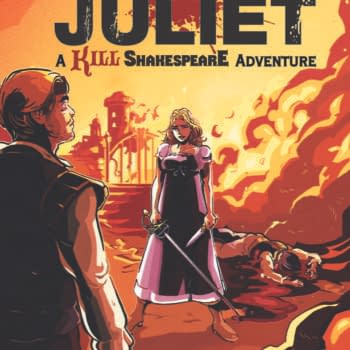

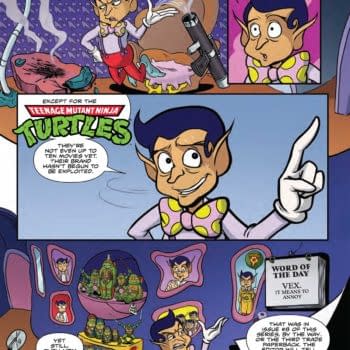

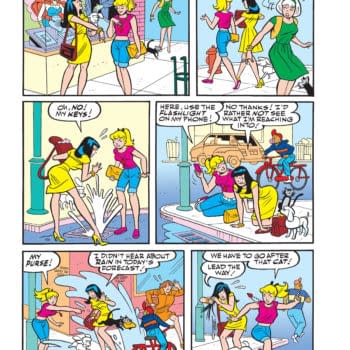

I think Moody's work captures that feel of turning the pages of a comic; the work evokes a sense of nostalgia, a nostalgia made more so because she has used real comics. For me, as a comic fan, the work is made more powerful for that reason. Her description of comics as inexpensive adolescent fare, printed for immediate consumption and disposal is how many of the children who read these comics when they were first printed used them. The work is not transformative or recontextualizing, it does not have to be, it dose not have to make grand statements. This is just as true for the comic book images as it is for Moody's Hershey Bar or the ticket stubs from her painting July. The work is however something new, appropriated though it may be. Within it you do not get the comic book as a story all you get is it as a frozen moment.