Posted in: Recent Updates | Tagged:

Pond Life by Martin Conaghan #8 – Done For Soliciting

Last week, we talked about getting your comic promoted, so this week, I'm going to have a look at pitching your work (again, all of this seems to be out of logical sequence, but it'll all make sense when I publish the collected Pond Life columns at some point in the future).

Essentially, there's two ways to pitch your work to prospective employers, and there's two different aspects of the any pitch to consider. The first is an out-and-out pitch made directly to an editor (usually in person, at a convention or other face-to-face meeting), and there's the remote method, via post or email. The two types of pitch are the idea behind your story (the written component), and the visual look and feel of it (the artwork).

I'll start with artists. First up: get yourself a website, a blog or other online presence where your most recent work can be viewed by prospective employers (services like Deviant Art and Blogger are good starts, but if you can get a half decent personal website built that you can update yourself, it'll look much more professional). Post to your web service regularly, and let the world see your work, and comment on it.

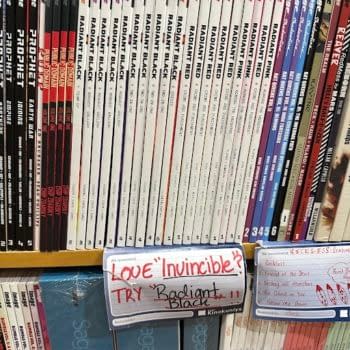

Secondly, buy yourself a big (and a separate small) portfolio folder where you can store recent samples of your work to take along to conventions – which, really, are the best place for editors to view your work. Consider the type of work you would like to do, and the companies that you would like to work for, then create samples accordingly – start with a cover to give your portfolio that 'wow' factor, then include appropriate mixtures of pencilled pages, inked pages, coloured pages and lettered pages, if possible. Again, try to arrange these according to the company or publisher you are targeting (for example, don't pitch Green Lantern pages to Marvel if you want to be the artist on the X-Men, and don't fill your portfolio pages with Mickey Mouse and Ben 10 if you're targeting Image Comics).

Most importantly, give an editor a feel for how you might approach one of their stories. Visit the Comics Book Script Archive and dig out a couple of scripts that might interest you (especially scripts of comics that you haven't actually read) and try to illustrate them – it'll give you a sense of how writers craft their stories and pace dialogue/action.

If you plan on attending a convention to pitch your work, try to make an appointment with the publisher/editor beforehand and be prepared to wait. Above all, when you finally get to the front of the queue or find yourself alone in the room with someone like Shelly Bond or CB Cebulski (look them up, if you don't know who they are), be courteous, polite – and accept any criticism they may have to offer. Whatever you do, don't leave any artwork samples with them (you'll never see them again, and they'll probably leave them behind), and don't dump your homemade comic on them (that's what postal mail is for).

Next, writers: the life of an aspiring writer is a solitary one, usually spent attempting to generate ideas from scratch without being derivative of the millions of ideas already out there in the wider media. It's also a bit of a Catch-22 in terms of pitching to companies; most of the big publishers will only accept pitches on invite, and will usually reject any unsolicited ideas aimed at franchise characters due to copyright issues. However, there are avenues of approach if you're willing to pursue them. Firstly, try to get something published, be it a self-produced comic or a five-page story in an independent anthology – and use it as a door-jammer; ie. post it to all of the mid-level editors at any publishing company you would like to work for along with a polite covering letter of introduction. If they like it, they'll get in touch. If you get no response, follow it up about a month later and enquire as to whether they've had a chance to read it. If you're lucky, they have – and if you're really lucky, they'll have liked it – and the door may open for you to pitch an idea or two.

Basic pitches should contain four essential items: a good title, a cracking one-line summary, a single paragraph pitch (back of the book stuff) and a broad treatment for the overall story – all on one page of A4. And it would help to include a few samples pages of script, to demonstrate that you understand the format of comic-book writing.

The chances are, your ideas will be rejected (this is normal), and you'll have to start all over again (get used to it). It's a long, slow process – but the fruits are there for the tenacious. (Note: tenacious does not include stalking, making repeated phone calls, resubmitting the same ideas under different titles or turning up at the publisher's offices unannounced).

The alternative is to befriend editors via fellow-creators and try to make a good impression over a period of time in order to persuade them that you're the writer they really want to hire, based on your endless ability to supply them with alcohol and funny one-line jokes in the convention bar (good luck with this approach – it usually leaves you bereft of cash and severely hung-over).

The other popular method of pitching a story to a publisher is to hook up with an artist who can spare the time to compile a few sample pages of your idea and create a snappy cover. Put it all together with your pitch document, your character treatments, some design sketches and biographical information of the creative team, then post it off to the big companies and wait for the offers to roll in.

But the most important advice I've ever been given about pitching artwork or stories to publishers is this: be nice, take advice and know when to give up and move on to the next guy.

If you can do all that and come out at the other end with a commission or a creator credit, you'll be a man, my son.

Martin Conaghan is a journalist and broadcaster at the BBC and a freelance comic book writer. The views expressed here are his own. He is also the writer of Burke & Hare.

Are you a small press publisher, writer or artist? Do you have something you think might be worthy of mention on Pond Life? If so, tell Martin about it at pondlife@copydesk.co.uk

You can request to follow Martin at Facebook or Twitter.